NEH Grant Will Allow VMA Professor to Complete Digital Banjo Museum

Filming for Give Me the Banjo with three of the greats — Earl Scruggs, Bela Fleck, and Tony Trischka — in Scruggs’ Nashville living room. Associate Professor Marc Fields is standing at left. Courtesy photo

By Erin Clossey

Visual and Media Arts Associate Professor Marc Fields wasn’t too far into filming interviews and gathering footage for his 2011 documentary Give Me the Banjo before he realized that he wasn’t going to fit more than 300 years of history into a 90-minute film.

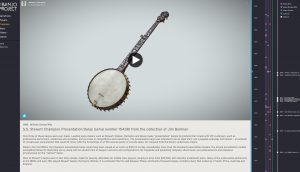

Much of the material he had amassed he left out of the doc — a process he called “painful” — but he turned it into a “digital museum” called The Banjo Project, an online cultural resource for anyone who studies, plays, or loves the instrument and its complicated history.

This week, the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) announced that it is awarding a $100,000 grant to Fields to complete construction of The Banjo Project. The site, hosted on the Emerson server, has been awarded numerous grants over the years from various cultural foundations, but the NEH funding will allow Fields to put the finishing touches on the project – as much as a museum is ever “finished”.

“It’ll allow me to …reach a point of completion and closure on the digital museum as a kind of online cultural resource,” Fields said.

Fields’ collaborator on the project is VMA Assistant Professor Shaun Clarke, who accompanied Fields on the project’s first shoot as a Concord Academy student in 2002, and was the associate producer for Give Me the Banjo. He is The Banjo Project’s production manager.

“His contributions to The Banjo Project have been crucial to getting this grant and to [the project’s] completion,” Fields said.

In the early 1990s, Fields – a classically trained pianist and self-taught aficionado of all types of music – co-authored a book with his father, Armond, From the Bowery to Broadway: Lew Fields and the Roots of American Popular Theatre, about an ancestor who was a turn-of-the-century theatre producer.

Writing the book immersed Fields in the landscape of early-20th-century popular entertainment — vaudeville, minstrel shows, and early jazz – and from there he gravitated to projects that had to do with theatre, jazz, and blues, he said.

With each project, he began to notice that somewhere, “either lurking in the background or part of the story,” was the banjo.

“I was trying to come up with a way of showing the history of American popular music and realizing [the banjo] was a very good vehicle for exploring the most redemptive and corrosive elements in American culture,” Fields said. “I came across the banjo as something that was kind of quintessentially American. Quintessential, because it embodies both the good and the bad as far as American culture goes.”

For almost 200 years, the banjo was primarily an instrument played by enslaved Africans until white Americans began incorporating it into their minstrel shows, Fields said.

The minstrel show, notorious for using racist tropes and blackface, also happens to be America’s first major cultural export, Fields said, and the banjo was introduced to mainstream audiences in the United States and abroad.

“That aspect of its history was initially what made it popular, but it also carries with it a lot of … damaging and distorting kind of caricatures,” he said.

Between the late 19th century and World War I, the banjo evolved into a darling of the salons of Europe and the American elite, who “whitewashed its black origins and tried to make it seem like it was more of a European instrument,” Fields said. This was the rise of ragtime, and every college had its banjo and mandolin club.

By the 1920s and ‘30s, the instrument had become a staple of both “race records,” recordings of early jazz and blues marketed primarily to African Americans, as well as the music of the rural, white, working class. This “old time” or “mountain” music became the basis for bluegrass, country, and folk music, Fields said.

“[The banjo] is a powerful icon with a lot of negative associations, but it also is a tool for artistic expression and cultural expression that has gone through a lot of different stages over a period of almost three centuries,” Field said.

Fields said he and Clarke have a vast amount of media content he wants to add to The Banjo Project, as well as different interactive features and content from partner institutions, such as the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University and the Smithsonian Institute.

“I see my function as kind of a curator for presenting stories [of the banjo],” Fields said.

Categories