Professor Emeritus’ Musical Debuts 75 Years After He Wrote It

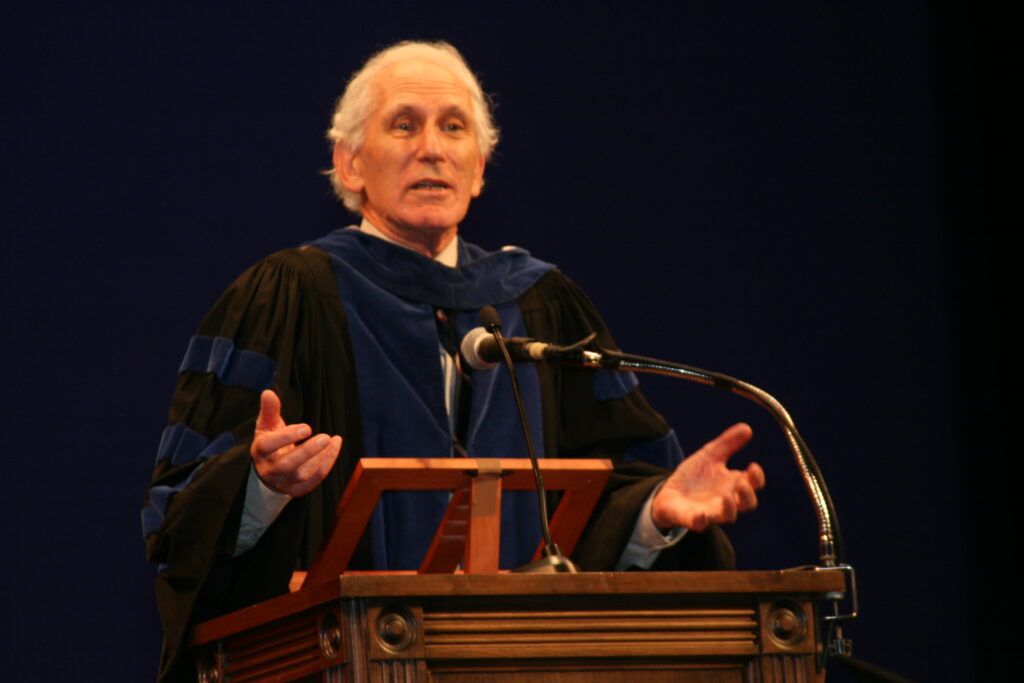

In 1949, Emerson College Professor Emeritus Robert Hilliard wrote Piccadilly, a musical about two American GIs on leave in London during World War II, and then the script rested in his filing cabinet for 75 years.

As Piccadilly lay unproduced, Hilliard came back to the States after fighting in the Battle of the Bulge at 19. He went to graduate school, got married, and worked as a journalist, educator, author, playwright, and humanitarian activist. He was Chief of Public Broadcasting at the Federal Communication Commission (FCC), the author of several books on communication and culture, and a professor and dean at Emerson.

“Over the years, I thought I really needed to do something with [the musical],” said Hilliard.

Fast forward to the 2020s, and Hilliard made a connection with the publisher of the Florida Weekly, who sponsored a production of the musical. After three-quarters of a century, Piccadilly debuted at the Laboratory Theater of Florida on December 28, 2024. Hilliard provided the script and lyrics, and worked with an arranger to create the music.

The musical is sort of based on personal experience. Hilliard had been wounded, for which he received a Purple Heart, and couldn’t go back into combat, so he started a military newspaper. He and another GI were on leave and visited Piccadilly Circus in London. They watched the sex workers, who approached Hilliard and his friend (both politely declined), interactions that gave Hilliard an idea for a story.

In Piccadilly, a straight-laced GI falls in love with a woman who, unbeknownst to him, is a sex worker. His (white) friend falls in love with a Black singer (in the 1940s, interracial romance was, in many places, considered taboo or even illegal).

While Hilliard’s visit to Piccadilly Circus provided inspiration for the musical, it was his real-life experience at the St. Ottilien monastery in Germany, where Holocaust survivors put on a concert, that pushed him to be a humanitarian activist.

“I sat there and cried like a baby, and I still do when I think about that experience. Most people were in concentration camp uniforms, and most couldn’t walk,” said Hilliard. “They put together an orchestra and played Jewish folk songs that were banned, songs of [Felix] Mendelssohn and other composers who were banned.”

But he also saw survivors still starving and wasting away. Hilliard and fellow GI Ed Herman decided they had to do something.

“We stole food from our own mess hall…people in the mess hall were unofficially selling it on the [bootleg] market,” said Hilliard. More survivors came to the location, so Hilliard recruited more GIs to help.

He and Herman began writing and sending letters to leaders of churches, synagogues, friends, YMCAs, and other philanthropic organizations, urging Americans to send boxes of supplies with food, medicine, clothing, and more, but nothing came. They found out that boxes had been sent, but were held up because President Harry Truman wanted to verify that people liberated from the camps were being neglected. Once confirmed, the boxes came, and the front page of The New York Times on September 30, 1945, featured Truman’s order to Eisenhower to help and provide the necessities.

Hilliard has carried that experience with him for the rest of his life, and stayed in touch with survivors. Even as he approaches 100 years old, he continues to speak publicly about the importance of humanitarianism.

“I tell youngsters, if you see something bad happening, don’t sit back and let it happen. We were two young soldiers. We had no standing. We stuck our necks out to try to save people’s lives,” said Hilliard.

Hilliard was approached by former Emerson College President Allen Koenig to be the Dean of Graduate Studies & Continuing Education, and began working at Emerson in 1981. Hilliard was working in government at the time and took a two-year leave to become dean of graduate studies. He ended up retiring from the government, and stayed on at Emerson. Not wanting to be in an administration position anymore, he segued to professorship.

Many of his own books were used in Emerson classrooms, including Waves of Rancor, in his course, hate.com, which focused on hate groups’ use of the internet to recruit and spread their message.

“Each semester the students put together their own websites in which they countered some of the principles and actions of the hate sites. We got media coverage,” said Hilliard. “We did innovative things at Emerson. The hate.com course got a lot of criticism, some parents didn’t like the idea of dealing with what was literally going on in the country.”

He also taught classes on communications law, and television and radio production. He was one of the first people to teach a class about the Holocaust and the media.

Whether it was working with students, faculty, or administration, Hilliard cherishes his time at Emerson.

“I went there for a two-year leave and spent 27 years there,” said Hilliard.

Categories