Up Close and Personal with Emerson’s On-Set Intimacy Coordinators

Before Mam Smith, MA ’95, began working as an intimacy coordinator, sex scenes in TV productions could play out very much like a one-night stand. Who knew what was going to happen?

Smith was one of the pioneers of a job that was born out of the #MeToo movement in 2018. A longtime and current stunt performer, Smith was one of the first to take on the role of intimacy coordinator, a position so new, many people still don’t know what it is.

“An intimacy coordinator is a professional who ensures that scenes involving physical intimacy and hyper-exposure—such as kissing, simulated sex, or nudity—are executed safely and respectfully for all involved, including the cast, crew, and production,” Smith explained.

Smith serves as a liaison between actors and the production team to maintain clear communication, establish boundaries, and create a comfortable environment for performing intimate scenes.

Smith’s first time as an intimacy coordinator was for HBO’s Westworld. She had just completed a program at the Irish Film Institute on how to direct intimacy on set. With her background in choreography on Broadway and stunt performing, Smith was a perfect fit for the role.

Going all the way back to to her days as a child gymnast, Smith’s always understood directing movement. As a stunt performer, she’s fought, driven cars, worked with fire, and importantly, she’s aware of her boundaries and comfort zone and performs only stunts she feels safe doing.

Smith said there’s a misunderstanding about intimacy coordinating.

“Ninety percent of the work is in pre-production. If I’ve done my work well, I should just be able to monitor,” said Smith, who’s been an intimacy coordinator for sexually-charged shows including Euphoria, Welcome to Chippendales, and Ruthless. “Some people see me monitoring and they don’t realize the hard conversations I’ve had with producers, directors, and actors. It takes strength to stand with integrity and sometimes pull these forces together or keep them apart.”

Emerson College prepared her for those hard conversations, said Smith.

“[Emerson has a] focus on communication. On a set, there’s 200 people sometimes. They have different ways of working and skills,” said Smith. “I can go in and read the room and know how to interface and adjust with the people I’m working with – I learned that at Emerson.”

Keeping actors apart or encouraging them to cool down is something intimacy coordinators may do on set, explained Alicia Topolnycky ’18. When people ask about her role, there is one dominant question: What happens if an actor gets excited?

“I always tell them, burps, farts, stomach rumbling, sweat, goosebumps, erections, nipples being hard, coughing, giggling – these are all in the same category of symptoms of using your body as an instrument,” said Topolnycky. “There is no shame associated with [any] of these things.”

While intimate scenes are choreographed days in advance, there are certain methods used on the day of shooting. She said the Theatrical Intimacy Education (TIE) organization encourages actors to say the word “button” if they themselves are uncomfortable, or if another actor is making them feel uncomfortable.

“They can do pushups to redistribute blood flow to move it from the groin. They could take five or take ten, or do jumping jacks, and come back when they’re ready,” said Topolnycky.

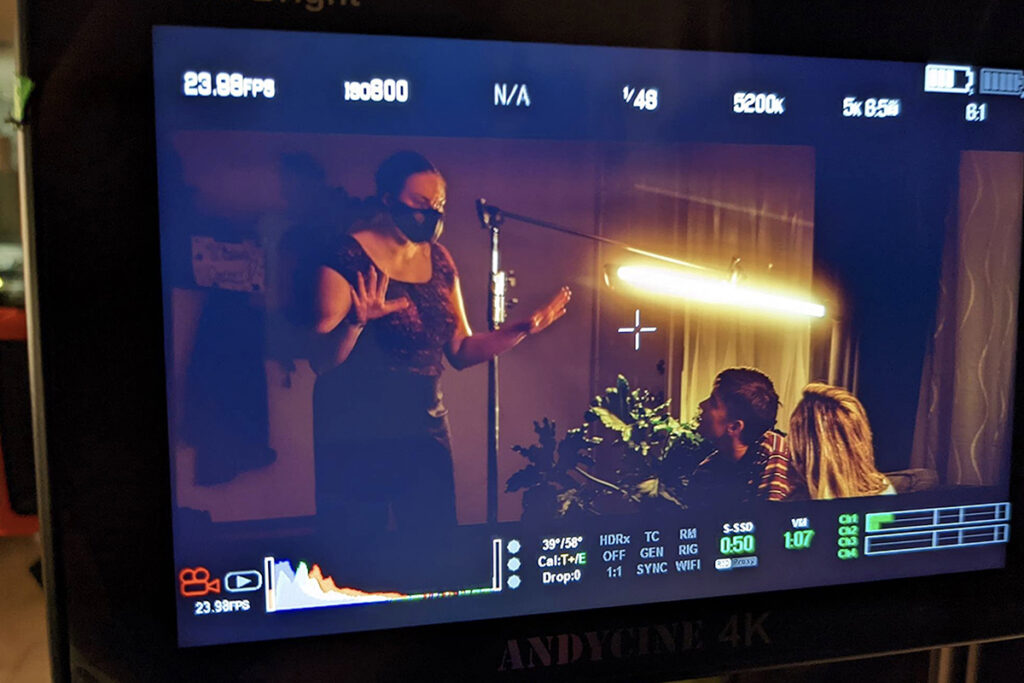

Topolnycky has been an intimacy coordinator for indie productions such as Honey & Milk, and she’s proud to work on low-budget films. She said in preparation of intimate scenes, she has actors face each other and touch themselves to communicate which parts of their body that they’re comfortable with being touched.

Consent is a huge part of being an intimacy coordinator, and part of the role is organizing informed consent documents.

Intimacy Doesn’t Just Mean Sex

Think about a scene when a kid climbs into bed with their parents. Or breastfeeding. Or using the bathroom. Masturbation. Menstruation.

“Sometimes I’ll be reading a script and say, ‘I need to be there for this scene.’ There was a lot of breastfeeding [in a recent show],” said Smith. “You have a naked baby getting washed. Babies are supposed to be naked in tubs. I talk to the mom and say what’s going to happen. ‘We’re not shooting genitalia, we’re shooting foam.’”

Smith described working on a scene that intimated pedophilia. She was instructed to be present and choreograph the scene, as well as get consent from the child’s parent and from the child.

“I talked with the child to frame it in a way a child could understand. I said, ‘He’s going to pat you on the head’,” said Smith. “I tell children that people can’t touch without consent. We weren’t technically filming an overtly physical scene, but because of the content, it was important for me to walk through the scene with the parents and child.”

Coordinating intimate scenes is something that was missing for decades in the entertainment industry. In 2020, the Screen Actors-Guild American Federation of Television and Radio Arts (SAG-AFTRA) mandated that intimacy coordinators be present on sets.

The role can also include working with an actor to move a little bit so the cinematographer can get a better shot. Smith said intimacy coordinators are a huge asset to productions because coordination of intimate scenes is often overlooked.

“Because of the stigma of sex and nudity, they don’t want to talk about it. Maybe they’ll spend 10 minutes talking about stunts in a production meeting, and then they say the characters are going to be in the shower having sex, and they say, ‘We’ll talk about it later’,” said Smith.

Topolnycky said intimacy coordinators also work with actors on de-roling. De-roling is the concept of stepping out of the world of the film at the end of the day.

“It’s separating the emotional burden of the character you’re portraying to something you’re internalizing,” said Topolnycky. “One de-roling exercise is to refer to yourself in the third person and list out all the things you did as the character that day. And in contrast, list all the things you’ve experienced as yourself today. We really try to examine where does lived experiences overlap with staged experiences. Where are there similarities? And more important, where are differences?”

Smith said performing stunt work for multiple decades taught her the ability to disassociate from the material.

“Sometimes you’re being killed or killing someone. I know it’s a game. It’s all a creation,” said Smith. “I’m not a method performer. I can be a part of it, and not of it. I’m not taking the actions home with me.”

Topolnycky said another mental aspect of an intimacy coordinator is when queer actors may not be out to their families, or they’re unsure of how the people in their lives will react to a film or role.

“We talk about the way the director is going to speak about the project in public,” Topolnycky said. “Whether they’re basically outing the actors, or I can help coach directors to refer to the actor and character as two different identities. The work carries onto post-production and distribution phase.”

Smith said while it’s important that intimacy coordinators not judge the scene or its content, there are things she wouldn’t want to make it onto TV.

“The harder the scenes, [that’s when] they need you the most,” she said.

Categories