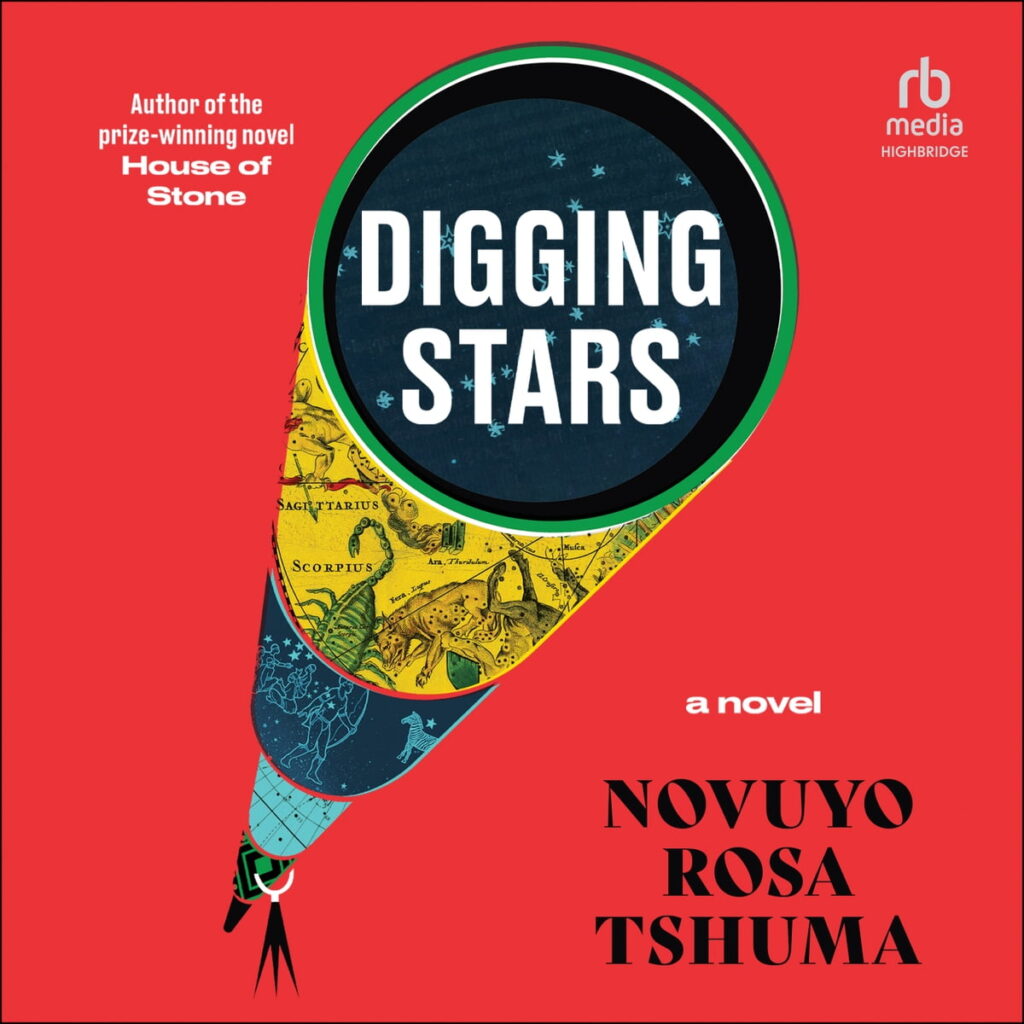

Astronomy and Geometry Star in Tshuma’s ‘Digging Stars’

Writing, Literature & Publishing Assistant Professor Novuyo Tshuma‘s second novel, Digging Stars, has garnered accolades as a “poignant story about loss.” Tshuma spoke with Emerson Today about the novel, astronomy, geometry, and the value of crossing disciplines.

What is your novel Digging Stars about?

Humans doing science—which encapsulates what has been demarcated as Western science and what is known as Indigenous science. Of course, when we find ourselves exploring Indigeneity, we inevitably find ourselves exploring colonialism. I was interested in capturing the spirit of the Latin root word, scientia, which means ‘to seek knowledge.’

What inspired you to write Digging Stars?

I wanted to understand this American society I now live in—much in the same way that, with my first novel, House of Stone, I wanted to understand Zimbabwe, the country I grew up in. Science offered a fresh and illuminating way to do this.

When we think of astronomy and space exploration, America as the center of cutting-edge exploration comes to mind. These ideas and values about life on earth and humanity’s future in space, about how we think about science, about who we understand as doing science, come to inform our collective imagination. I wanted to explore this. I decided to put a group of graduate students—Indigenous students, Black students, white students, and international students all passionate about science—in a confined space and have them grapple with these questions.

Astronomy is a major component of the novel. Is astronomy a personal interest of yours? Why is astronomy important in the telling of the story?

I took on astronomy as a hobby, and it evolved into a passion. I was curious about our evolution from the stars. I love Western science’s original premise, which is that ignorance—admitting what one doesn’t know instead of hastening toward an answer—is the starting point of attaining knowledge. I was also perplexed by Western science’s own blindness; despite its claims to objectivity and uncovering ‘truth,’ Western science has been complicit in some of the gravest atrocities in history, such as the dehumanization and subsequent genocide of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas and the ongoing devastation of our planet. I wanted to explore this experience, the experience of practicing science in a contemporary context, which becomes, inevitably, the experience of colonialism. Western science has no doubt given us many great and astonishing wonders; what it seems loathe to do, however, is take responsibility for its devastation.

I found, in Indigenous science, transcendence—an awakening to and endless wonder about the world around us. This can be found in Indigenous tales, whose stories about the night sky are also about goings-on here on earth. There is a fine attunement to this symbiosis between sky and land, an effortless recognition of our interconnectedness to all that exists—from the stars to the trees to, yes, fungi (a preoccupation in Digging Stars). This is embedded in the language, in the worldview, and in the science. I was able to see, through the work of Indigenous scientists in North America, similar ideas at play in Indigenous Africa. I found this exciting.

I was astonished that America can be embedded with so much richness—a richness of languages (I tried learning Hopi while writing Digging Stars), of worldviews and knowledges—and yet be so careless with, so callous and oblivious towards this richness. This, of course, is the legacy of colonialism, which despises that which it fails to subdue or destroy.

I was saddened by the fact that growing up and learning about America as told through its stories and movies and songs, I never knew or learned about its Indigenous peoples. Indigenous nations do not even appear on the world map. I was even more astounded to learn that our rural homes in Zimbabwe where our ‘true, unspoiled cultures’ are said to reside—what we call ‘amareserve’—were modeled on the North American reservation. Once I discovered this, I could not look away.

An innocent foray into science turned into an enchanting journey into history and into humanity, uncovering connections and making new discoveries. This is what I love most about writing.

In your novel, you talk about Bantu geometries. Could you say more about this?

In thinking about Euclidean geometry—in how the Greeks conceptualized space—I became interested in other geometries, in how other cultures have conceptualized space. We know that the Greeks dreamed of a perfect geometric world. According to them, our material world, with its perceived chaos, was but a lesser world and ought to aspire to this perfect geometry. These values of a degraded world came to inform much of the values of the Western world. They spread to the rest of the world through colonial conquest.

We see the values of a perfect geometry everywhere around us; from geometrically designed mono-crop landscapes weeded of their biodiversity; to the geometry of race expressed through notions of racial purity and segregation; to the geometry of modern cities, and in particular, settler colonies—walk through the city of Bulawayo in Zimbabwe, for instance, and feel the power of this geometry as you traverse the wide, straight boulevards; converge upon the seat of authority, the imposing City Hall with its Corinthian columns and geometric gardens; everywhere straight lines and angles, hierarchy and order; you are experiencing a Euclidean colony.

Bantu geometries in Digging Stars is a modern concept. Frank, the Ndebele astronomer, is inspired by Euclid. As we know, Euclid didn’t actually create a new geometry. He collected the mathematical concepts and geometric ideas that had been formulated by various Greek thinkers over time and distilled these in his seminal work, Elements, to create a unified body of knowledge. Frank sees himself as attempting a similar kind of work, translating the geometric practices of the Bantu—how they conceptualized and moved through space—and distilling these into a treatise.

The actual maths at its most basic level remains the same. It is the expression of the mathematical ideas—what one creates with that maths, with that science, that differs. In Digging Stars, a Ndebele astrophysicist, an Afro-Choctaw biophysicist, and a Haitian-American computer programmer come together and experiment with imagining a world into being.

How has your experience of writing a novel helped you be a better educator?

Digging Stars has made me question the artificial demarcations between fields such as science, art, and history. Who benefits from these demarcations? They are certainly to the detriment of our collective humanity. We become sharper, perhaps, and certainly profitable to those industries that launch knowledge with the precision of a space missile—but we also become narrower and, to me, a little less knowledgeable about one another and our world.

A very complimentary New York Times review of your book asked: “What compromises are we willing to make to achieve our highest ambitions and how much do we owe our own history?” Can you answer those questions about yourself?

Those are big questions, philosophical questions. I think it’s great that Digging Stars asks these questions. I think fiction, at its most fundamental, poses questions rather than offers answers. In this way, fiction provokes thought.

Categories