Alum Sara Novic on Transformation, TV, and Telling Authentic Deaf Stories

Sara Novic ’09 is an author, professor, translator, and deaf rights activist. Now you can add executive producer to that list.

Novic’s second novel, True Biz, due out in 2022, is being developed for television with actress Millicent Simmonds (A Quiet Place, Wonderstruck) signed on to star and EP.

True Biz, set in a boarding school for the deaf, follows a student, her teacher, and her friends through a year of romantic, political, and personal upheaval.

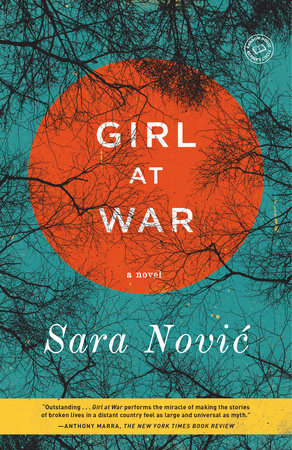

Her first novel, Girl at War, won an American Library Association Alex Award, was an LA Times Book Prize finalist, and was translated into 13 languages. She teaches a writing workshop in Emerson’s Popular Fiction MFA program, where she is a thesis advisor, and she teaches an introductory Deaf Studies course at Stockton University in New Jersey.

Emerson Today asked Novic about the TV deal, writing as a D/deaf author, and what she learned from Emerson.

What does the title True Biz refer to?

“True biz” is the transliteration (in linguistics we call it a “gloss”) of an American Sign Language (ASL) idiom. It can mean a few different things depending on the context, but some of my favorite English comparisons are “real-talk,” “seriously” or “deadass.” In the book, the phrase pops up in slightly different ways as the plot progresses, so I’m hoping that’ll be a nice easter egg for readers to track as they move through the story.

When you were writing the novel, did you/could you envision it as a television adaptation or has this come as a complete surprise?

I think I’m a pretty visual writer—I’ve been told that my writing is “cinematic”; I do think that stems from being an ASL speaker, and the visual-spatial power of that language. I do try to picture everything in 3-D in my head so I can render it vividly for the reader. That said, while having an adaptation of my book is definitely a dream, it wasn’t something I was expecting to really happen at all!

How did this adaptation come about?

My agent is the actual Superwoman.

Also, given the interest we saw in the project, it’s clear there’s an appetite for something a little bit different. I think TV is looking for new and diverse ways into universal themes right now, and the novel is fully both of those things. Most people don’t know much about Deaf culture, but everyone’s familiar with a version of the love and loss inherent to coming-of-age stories, so this offers a new lens at which to examine that.

Is this being developed as a TV movie, limited series, series?

Right now, we’re developing the project as a TV series, but the field is wide open as to whether it will be limited or something that could go on past the bounds of what’s written in the novel.

How much are you be collaborating with Millicent Simmonds and the creative team on this project?

I’m really excited to have the opportunity to work closely with Millie and the Circle of Confusion team on this project as an executive producer. If the show moves into production, I’d love to be part of that on the writing side, too.

I think it’s kind of unprecedented to have two Deaf female producers on a project, and though we’re still in the early days in terms of development, I love that we’ve got a united vision about what this show should and could be.

You’ve written in The Guardian that due to a number of factors, including spoken/written English being a second language for many, there is a paucity of fiction written by d/Deaf authors. As a Deaf writer, how keenly have you felt that, both in terms of the kinds of stories you read and the lack of role models?

I feel a little conflicted about this piece today—on one hand, there is certainly an underrepresentation of d/Deaf writers and authentic Deaf stories in the literary world (and in Hollywood). On the other, I think a lot of those feelings of isolation were stemming from my experience in an MFA program where I was the only Deaf person, and was feeling that singularness acutely. When you only read stories for and by hearing people, you can get to thinking that what you have to say isn’t “literary,” which is why representation matters so much.

In the years since, I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know more Deaf writers, artists, and journalists, and have realized, of course there are many of us—the real question is whether the literary world will step up and champion those stories.

Both True Biz and your first novel, Girl at War, are coming-of-age stories. What is it about childhood/adolescence that attracts you as a writer?

People are so quick to relegate stories featuring young people into a “YA” category, and I want to push back against that. When you’re young and feeling everything so full-on, that’s when the capacity for change is at its greatest, and what’s more interesting in fiction than a character transformation? American culture is often dismissive of, or condescending to children and young people, but we have a lot to learn from them. I always say that I’ll stop writing about kids and teenagers when they stop teaching me things; they haven’t yet.

For Girl at War, it was a bit more straightforward, because I was only 18 or so when I started writing it. It was also important to me that a story about war be centered around the people who suffer the most and are the most ignored during conflict—women and children. With True Biz the story is more evenly split between coming-of-age and approaching middle-age, as the student protagonist and the headmistress act as foils for one another through the novel.

How has Emerson shaped you as a writer and/or an activist?

Emerson changed me indelibly—as a human, writer, and activist. My WLP professors gave me the confidence to see myself as a real writer, rather than a person who writes stuff. Girl at War was originally a short story I wrote for Jon Papernick’s workshop. So many of my writing and literature teachers were supportive of me, and were willing to answer my endless questions in office hours, and to lend me books. The Disability Services Center [now Student Accessibility Services] knew what I needed before I did. The small, tight-knit community was really what I needed. I would never have even tried if it hadn’t been for my professors. Also, I sure am glad I took Chris Keane’s screenwriting class now!

Emerson also made me an activist. I wasn’t born deaf, and when I started losing my hearing, I had never met another deaf person before. In isolation, I saw myself as hearing people saw me—someone who had once been “normal” but now needed to be fixed. As a result, I spent a lot of time being ashamed and trying to hide my hearing loss. As I began a deep dive into all the theoretical texts that were the foundation of the Honors Program at Emerson, the concept of socially-constructed identity, and socially-constructed, systemic barriers rather than inherent shortcomings within people, radically transformed my understanding of myself and the world around me. That new understanding, coupled with the vibrant Deaf community in Boston, not only allowed me access to ASL and Deaf culture, but also made me want more for other deaf kids. That was where my activism started—a desire that deaf kids could grow up unashamed, and with full access to language, and knowing they weren’t alone.

What are your hopes for the TV adaptation of True Biz?

My hope is that this show stays authentically Deaf, and doesn’t get watered-down to be more palatable for hearing people, and that it’s loved for that.

For me, a big part of this means showing the reality of the Deaf community as an extremely diverse population with respect to race, ethnicity, class, gender, and sexual identities, as well as ways of interacting with sound and language. The Deaf community is unique because of the multiculturalism and varied experiences that are connected via American Sign Language, and I want that to be at the forefront of this story.

The thing that really excites me about having Millie on board is knowing that we have a phenomenal Deaf actor playing a Deaf character. That’s the goal for all the deaf roles, and well as ensuring deaf people are involved throughout the production process behind the camera, too.

What are you working on now?

At the moment, I’ve been writing short stories for the first time in years, which has been nice. I can’t write multiple fictions simultaneously, so while writing True Biz my fiction brain was wholly consumed.

I’m also working on a nonfiction project—a mashup of memoir and critical theory that will examine Deaf culture and history, language, and identity, in the form of letters to my young son.

Categories