Reflections on MLK’s Legacy, January 2021

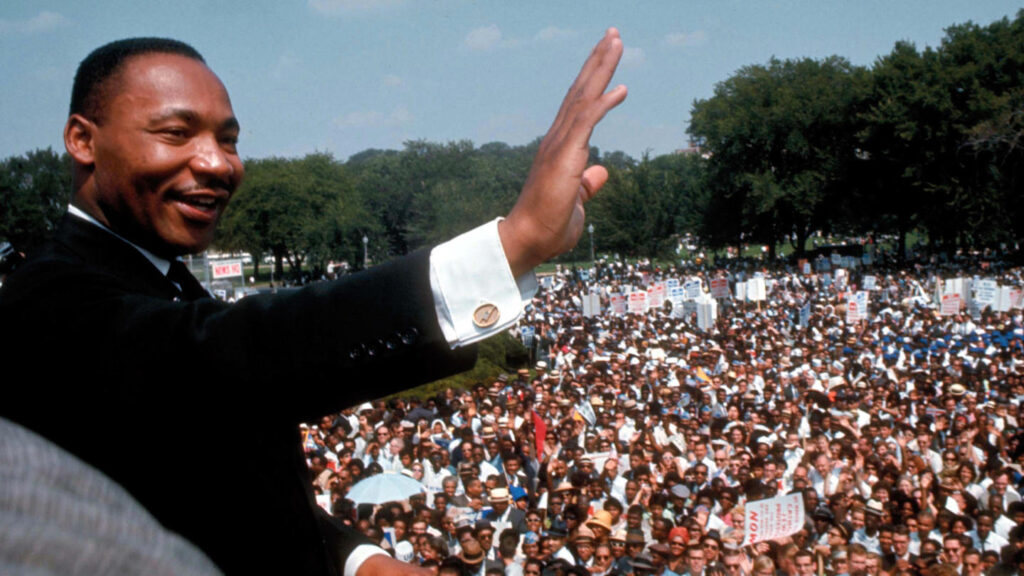

Each year, since Raul Reis became dean in 2016, the School of Communication has hosted a celebration of Dr. Martin Luther King’s legacy. This January, instead of an event, Reis asked members of the SOC faculty to join him in sharing reflections on Dr. King’s legacy in light of the issues and events of this extraordinary time in history.

Mr. Evans

By Lina Maria Giraldo, Assistant Professor, Journalism

Coming from Colombia, my first home in Boston was in Roxbury’s heart, in an old brownstone. On the first floor lived Mr. Evans, a tall, older man with deep white hair, losing his hearing and eyesight. He was always there to help everyone and greet us with a smile. One morning, Mr. Evans was standing proudly at the entrance of the building. He looked in my eyes and asked if I knew that it was Martin Luther King Jr. Day. He then told me his story:

He was a young man in Alabama when the Montgomery bus boycott started. Every day for a year, he refused to ride the bus and instead walked for more than two hours to work. Every day, there was a line of police officers with aggressive dogs trying to force them to get into the buses. He would pass them without engaging. Then, it was a silent line of women and men walking on the side of the road for hours. After nine hours of hard work, they would walk back again for hours to arrive home with feet full of blisters.

At the moment, I didn’t realize the lasting impact this story would have on the rest of my life. I had recently arrived, was learning English, and didn’t entirely understand what segregation or racism meant. Suddenly, I found myself inspired by a community that forged their future as Dr. King had once encouraged them to do. A legacy of imagining our path defined not by the color of our skin, but by the content of our character. Today, more than ever, this shapes my essence as an immigrant, creator, storyteller, citizen, and journalist. It sets my responsibility for telling the stories of the unheard, the underserved, and all those mistreated.

A Tribute to Georgia’s Ebenezer Baptist Church – From Martin Luther King to Raphael Warnock

By Roger House, Associate Professor, Journalism

A measure of a civilized society is the institutions it builds to preserve and continue a legacy. For African Americans, one such monument is the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta – founded 135 years ago by people recovering from slavery.

As we observe Martin Luther King Day, people at home and abroad cheer the arrival of political change in Georgia and America – even as they condemn the violence that threatens our democratic institutions. In the midst of chaos, the Rev. Raphael Warnock’s triumphant campaign for the Senate has affirmed the promise of America. His platform of justice and moderation was a testament to the legacy of Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Warnock is the fifth minister of Ebenezer Baptist Church, taking charge in 2005; more importantly, he is the first to achieve the full measure of political redemption demanded in the long struggle for Black freedom. His election made real the dream of voting rights championed by his most renowned predecessor, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

King was the co-pastor of Ebenezer from 1960 until his assassination in 1968. Under his direction, Ebenezer forged a network of activist Black churches known as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The SCLC was a crusader for racial justice and the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 1965 Voting Rights Act, and 1968 Fair Housing Act.

King shared the ministry with his father, the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr. The beloved “Daddy” King led Ebenezer from 1931 until his death in 1975. He married Alberta Christine Williams, the daughter of the preceding Ebenezer pastor, Adam Daniel Williams. She gave birth to Martin Jr. and helped to guide the church in espousing a philosophy of economic self-reliance and spiritual relevance.

In turn, “Daddy” King’s vision of the role of the church was influenced by his father-in-law. In 1894, “A.D.” Williams assumed leadership from John A. Parker, a former slave and the church’s founder. From 1886 to 1894, the Rev. Parker directed a fledgling congregation of 13 in spiritual fellowship and mutual support at the “Ebenezer.” The word refers to an Old Testament story about a stone marker used by the Hebrew people to remind them that God would protect them and guide them to victory.

Note: This submission was adapted from a longer essay that appears in the The Hill.

Different Ships or Same Boat Now

By Cheryl Owsley Jackson, Journalist-in-Residence, Journalism

This year, on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday, we have a chance to relate to his struggles through the fight for equal rights, more than any time in recent history. This year, many Americans mark the occasion feeling beaten down, emotionally drained, shocked, confused, wounded, and betrayed.

Less than two weeks ago, after four years of incendiary and divisive rhetoric from the highest office in the land, a violent insurrection took place at the U.S. Capitol. As Confederate flags were paraded through its halls, and law enforcement responded with a fraction of the force with which it met peaceful civil rights protests this summer, America saw not just racial inequity, but the evil faces of white supremacy.

This mob, fooled by conspiracy theories and fueled by racism, may have been invisible to many Americans until this moment. But not to Black people. We have always known they existed. If we haven’t met these bigots face-to-face — and most of us have — their violence is alive in the stories of our ancestors.

In this moment, it be would be easy to conclude that the work of Dr. King has gotten us nowhere. There’s still angry division; still high-level, violent, racial strife; and still blood in the street.

I do believe there has been progress toward Dr. King’s dream of unity, although difficult to see through the urgency of public prejudice. We are not where we should be, but we are not where we once were.

We recognize the allies of all races who have marched in streets and taken a stand for Black Lives Matter, after George Floyd’s slow, brutal death instigated a new revolution.

We recognize those willing to risk police violence to align themselves with the movement, and the BLM signs in yards, on hats, and T-shirts worn in public, leaving no question they are allies.

We recognize the organizations, churches, synagogues, and mosques also standing up for Black lives. Many organizations are making this public statement for the first time.

We recognize the consequences of a nationwide calling-out of the “Karens”—women who use their white privilege against people of color as a tool of power, to reprimand, to control, or worse.

It seems we are at the end of something, and the beginning of something else, though both places in time are hard to define. Maybe this could be a beginning for people who have fallen into the muck of prejudice, now waking up to make legitimate change.

Some endure heartbreak, as we realize people with whom we have shared our lives harbor deep-seeded secret prejudices that, in this climate, they could not keep quiet.

Of course, some betrayals are so egregious there is no way to recover from them, but maybe there is hope for coming back together with those who want forgiveness, are ashamed of their prejudice, and demonstrate true change. As Dr. King once said, “We may have all come on different ships, but we’re in the same boat now.”

On Resolutions

By Brent Smith, Professor and Chair, Marketing Communication

For much of the world, it is a common practice to set New Year’s resolutions. For example, we resolve to improve our diet, cease a bad habit, restart a fitness program, or get more involved in the community. Moved by something that piques our interests, feeds our ambitions, or speaks to our spirits, we understand that this annual ritual can help reset our sense of agency to make meaningful things happen.

René Descartes noted, “I think, therefore I am.” When we think about our resolutions, we might wonder if we have the faith and courage to achieve the results. I humbly propose that we consider the following idea: “I resolve, therefore I believe that I can.” While we are now chronologically beyond the Year 2020, we certainly know that it gave us many challenges, or opportunities, to examine the priorities evident in our interests, our ambitions, and our spirits.

As we begin 2021, we honor the life and legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a person who made it his annual daily resolution to answer what he regarded as “Life’s most persistent and urgent question, ‘What are you doing for others?’” Indeed, if we resolve to take up this question each year each day, then we can make more meaningful things happen!

Hope and Optimism

By Raul Reis, Dean, School of Communication

We would have to go all the way back to 1999-2000 to find a new year transition as momentous and full of expectation as this one. As we wrapped a most unusual and convulsive year, we got reassuring news about the COVID vaccines, even as a new surge threatened to wreak havoc on our healthcare system and on countless families.

The election of a new government also sent a wave of hope and optimism to millions of Americans concerned about our democratic system, the freedom of our media, and the moral and physical health of our battered country. Sadly, for millions of other Americans with opposing viewpoints, that same election has led to anger and despair. Nonetheless, keeping a healthy dose of skepticism and critical inquiry, we must look at this transition of power as a sign that our democracy is intact, and hope for better days of empathy and equity, justice and the rule of law, accessible healthcare and peace, among many other things.

Looking closely at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and legacy, we draw inspiration from his own optimism about the future. Dr. King’s optimism was informed by his faith, his sense of justice, his historical perspective, and, I would argue, most of all by his audacious and boundary-shattering imagination. Only someone as intelligent and imaginative as him could, in 1963, deliver a speech such as “I Have a Dream,” which rivals and complements Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address for the precise and concise way it simultaneously illuminates and shatters our reality, casting a long, optimistic beacon of light into the future. In the case of President Lincoln, into our future as a nation capable of thriving and inspiring other nations. In Dr. King’s case, into our future as a human race.

My father was a lawyer who defended several political dissidents in Brazil. He deeply admired and found inspiration in Dr. King, often referring to him and John F. Kennedy as the best examples of what leadership really meant — and what, in his view, America really meant. I certainly have that in common with my father. As an immigrant to this country, as someone who chose to be here, I can’t help but to be optimistic about the future, and about this promise of America.

May Dr. King’s words, actions and legacy inspire us every day, as we strive to achieve a truly equitable and just society.

Categories