Virtual Reality Filmmaking Coming to Emerson’s Boston Campus

Next semester, Associate Professor of Visual and Media Arts Daniel Gaucher will be teaching his film students to forget about what they’ve learned so far.

In the spring, he will begin offering a course in immersive filmmaking—something he’s been working on over the last few years and has taught as directed study in the past. It will be the first formal “virtual reality” class offered on Emerson’s Boston campus (Emerson Los Angeles launched one in Spring 2016).

“It’s quite difficult as a medium, because it breaks the rules,” Gaucher said.

As someone whose professional background is in editing, Gaucher said he has had to be fully aware of all the formulas and rules that make good traditional filmmaking. For instance, the editor will use a particular sequence of shots called “formula editing” (wide shot, medium shot, over-the-shoulder, close up) to build intimacy for an audience, he said.

With immersive filmmaking and virtual reality, “we have to think of ways to get that same psychological reaction now without so many edits, and without being able to manipulate the camera [in the same way],” he said.

(Some definitions: What Gaucher is teaching is more accurately called “immersive filmmaking,” where the viewer is positioned in the midst of the action but cannot determine what happens in the film. “Virtual reality” technically refers to experiences in which the viewer has agency. “Augmented reality” is a medium in which virtual reality, or VR, elements are superimposed over actual people/places/things. For the purposes of this article, VR is used as a catchall term.)

Gaucher compared where filmmakers are today with virtual reality with where the 19th-century founding fathers of filmmaking were when they would just stick a camera on the street and record what passed in front of them.

“We’re kind of back at the Lumiere Brothers stage,” he said.

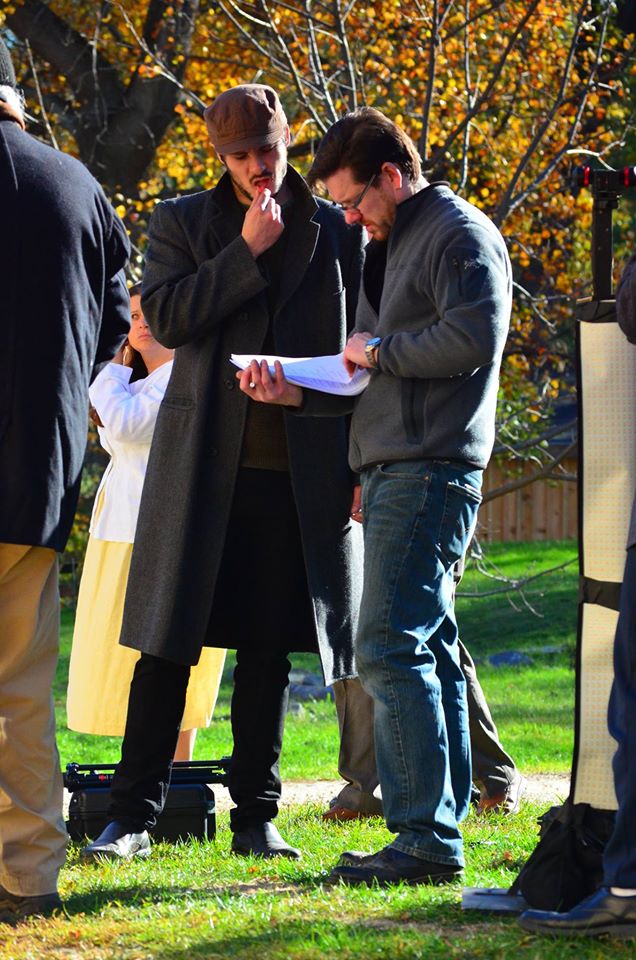

That might be a bit of an exaggeration. Gaucher, along with Alexandre Echeverri ’15, former student Brendan Feeney and some current students, is testing the narrative waters of immersive filmmaking with Maren’s Rock, his retelling of the 1873 Smuttynose Island axe murders.

The narrative short being filmed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, dramatizes the double murder of two Norwegian immigrant women, witnessed by another woman who hid all night in the rocks on the island’s edge. A German fisherman was convicted and hanged for the murders.