5 Things to Know about Empathetic Teaching

By Melissa Russell

In each class he teaches, Dr. Jae Williams ’08, MA ’16 begins with a question: “If you could have dinner with anyone, living or dead, who would it be?”

The exercise may sound like an icebreaker, but it’s much more than that. As students gain insights to each other’s personalities, they also begin to build the foundation for a community they will share for the next semester…or longer.

With the right sense of community, Williams believes, as students build relationships through authentic connections, they also prepare to solve real-world problems through empathy, passion, and collaboration.

Williams has given this subject a lot of practice and thought—as an award-winning educator, writer, and podcast host—and has shaped his own philosophy, “TEACH WE,” which provides us seven things to know about his approach to empathetic teaching.

Does it work? Only his students can say, but according to one recent course evaluation, “The content was great, but what made me love the class was that you made me feel like I was part of something bigger.”

1. Tailor content to meet students’ needs.

“My syllabus isn’t done until I’ve met the students and asked them what they want to get out of the class,” Williams said. Because every student needs a different level of attention and opportunities, and because every student learns differently, Williams first ascertains if the class is appropriate for the student, and then creates an environment where they are comfortable sharing and collaborating.

2. Engage students with real-life applications.

Williams leverages connections and relationships with industry professionals, and has students work on projects that allow them to see how their work would be viewed in the marketplace of ideas while they are still students. He wants his students to understand what skills they will need to thrive in the professional world.

“Students need an opportunity to see where they sit in the talent pool,” he said.

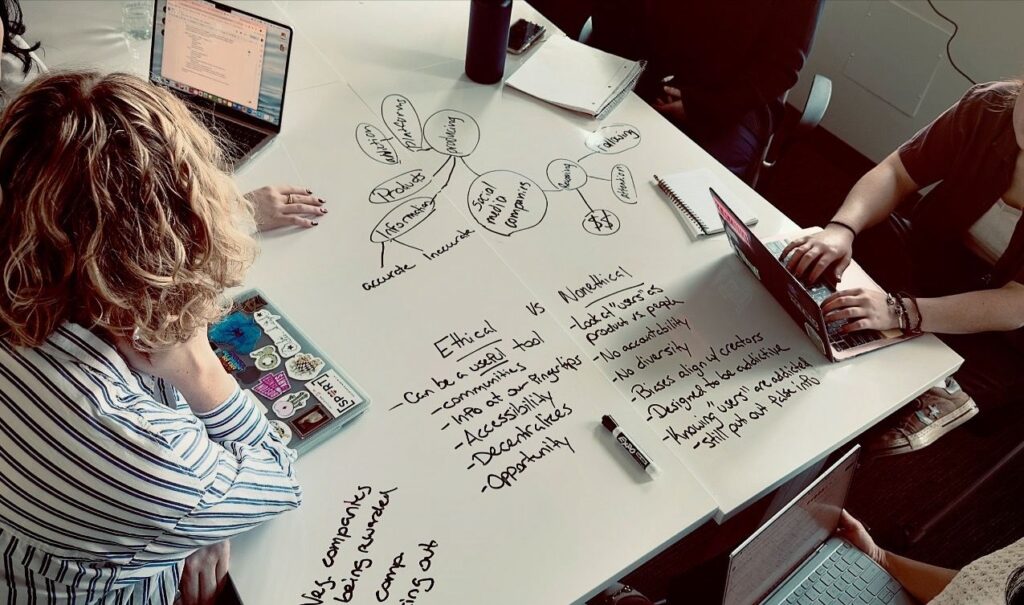

3. Activate creative thinking through collaboration.

Williams has students swap laptops in the classroom so they can read each other’s papers to identify similar themes and concepts. “Students get a chance to see the same thing through a prism, versus one lens,” he said. Collaboration leads to opportunities for asking better questions, Williams believes. “Can this be better? It’s a good idea, but can it be a great idea?

4. Create a “brave” space.

A brave space is different from a safe space, Williams said. Safe spaces don’t exist in the professional world. Creating a brave space, where students are empowered to voice their opinions, especially when difficult topics arise, is far more important. A brave space gives permission to be wrong or to say the wrong thing if “their heart is in the right place, but their mind is not,” and provides the opportunity to recover from mistakes. “At the end of the semester I hope I’ve made better humans, versus better students,” he said.

5. Harness curiosity through questions and dialogue.

Encouraging curiosity through asking questions is crucial, Williams said. When students feel comfortable enough to ask questions, they become more engaged and take their learning outside the classroom.

As promised, Williams added WE as an added bonus.

6. Witness growth through feedback.

One of the most fulfilling parts of being an educator is witnessing students grow during a semester. It is important, Williams said, to help students recognize what they are good at so they keep growing. Instead of pointing out errors, educators must give specific, personalized feedback on how to improve. “You’re really good with words,” or “You’re really good with imagery,” or “You’re amazing at presenting but your words mess up your energy. How about if you tighten your words up a little bit?”

7: Embrace empathy

Possibly the most important element of the TEACH WE framework is the final one: embracing empathy.

This is how you subtly place empathy in a class culture, Williams says. “Now that students have had a chance to know each other, it is part of the oxygen in the room.”

The ultimate goal, Williams said, is to create a generation of life-long learners who will take on the worlds’ problems with new energy and focus.

He explained, “We want to be able to pass the baton to people who are thinking about what’s around the corner, so we can rest, like the generations before us.”

Categories