Military Veteran Lauren Johnson Takes Off the Camouflage in Debut Memoir

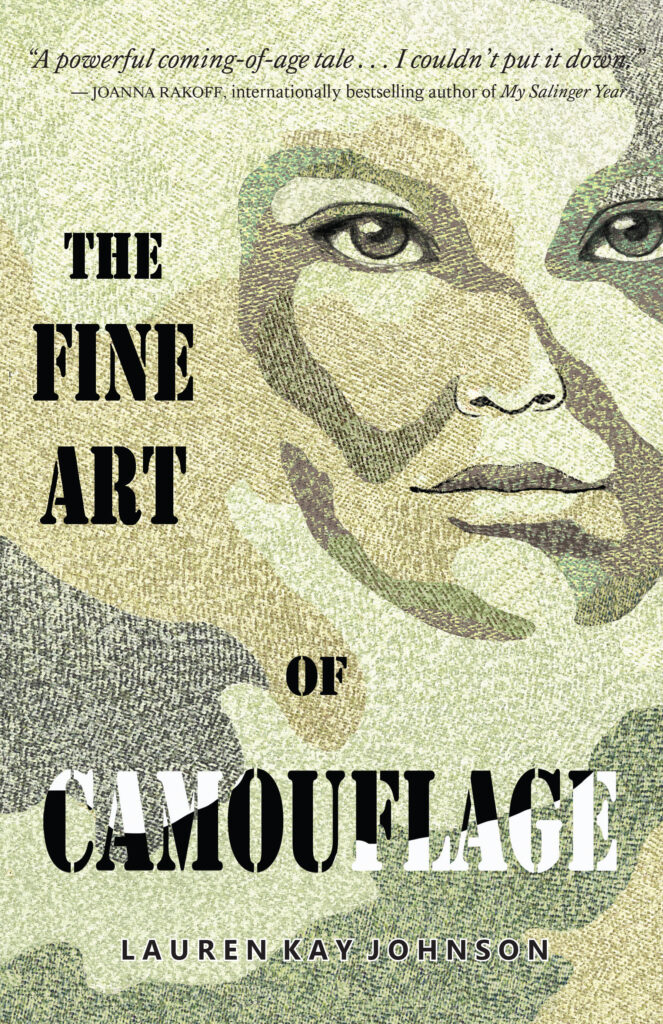

Lauren Johnson’s (MFA ‘14) debut memoir, The Fine Art of Camouflage, is a coming-of-age story about growing up in a military family and and exploration what it means to be in the military.

Johnson spoke to Emerson Today about her memoir, the word ‘camouflage,’ the book being on the cover of Penthouse, and her Emerson graduate experience.

Q: When did you begin to think about writing this memoir?

Johnson: I started writing about my military experiences as I was applying to grad school. I had a vague vision of maybe it would shape itself into a book at some point. I kind of had these little snippets about my experience and it was very fresh at that point. I had only been back from Afghanistan for about a year. So it was definitely more like spilling my guts, purging myself of that experience and just starting to shape it into something meaningful.

Starting at Emerson, I was able to get really helpful feedback, a lot of encouragement, which was so important in that early stage when I was trying to figure out what I was doing and didn’t have any concept of what the publishing industry was like… The encouragement was to just keep writing and let the writing lead you to where it needs to go, and over my three years at Emerson, it started to develop more into some kind of book-like thing that became my thesis. Then, once I graduated, I really was able to focus in earnest on taking all of this feedback I’d gotten for the beginnings of a book and start to really hone in on what it wanted to be and to start to shape it. It took another decade or so but we got there.

Q: Were there any particular courses or professors at Emerson that you found especially helpful?

Johnson: Yes, big shoutout to [Writing, Literature & Publishing Professor] Jerald Walker, who was the chair of the Writing, Literature & Publishing Department when I first came to Emerson. He actually called me after I had received my acceptance offer and asked if I had any questions or if anything would be helpful to know about the program, and that personal outreach really meant a lot. It made me feel – ‘desired’ is a weird word – but it made me feel like they wanted me at Emerson and that they felt I could add value to the program and that I could get value out of the program.

I did go on to work with Jerald as a professor, and then he was my thesis advisor as well. He helped me in a lot of ways that I needed to be helped, the big one that sticks with me is how to kill my darlings, which is a publishing phrase to trim the fat from your writing and eliminate unnecessary details or unnecessary scenes, unnecessary 100-page chunks, as the case may be. I still hear his voice in the back of my head as I’m editing my writing like “Do you really need that?” So that has stuck with me.

All of the other professors I worked with in the nonfiction program: [Professor] Jabari Asim, [Professor Emeritus] Richard Hoffman, [Professor Emeritus] Doug Whynott. [Former affiliated faculty] Joan Wickersham, I worked with for a semester there. [Senior Affiliated Faculty] Delia Cabe, I had her for a class and she has continued to be a great support system for me as well. I‘ve kept in touch with folks. Jerald blurbed my book, which felt kind of full circle to get to that point.

Q: Tell us about your experiences being published in literary journals.

Johnson: I think my very first creative writing publication happened toward the end of my first year, in a literary journal, and I also won a national essay writing contest in Glamour magazine while I was at Emerson. And that piece had been workshopped in my Emerson nonfiction workshops, so that was my first big exciting, ‘Hey, I’m a real writer!’”’ moment. It was nice to be able to share that with the folks that helped me craft that.

I also worked on the staff of Redivider, which is the graduate student produced literary journal. I was the editor-in-chief there my third year in the program. I learned a lot just about the behind-the-scenes of what goes on with receiving submissions, reviewing submissions, and how the logistical publishing of a regular literary thing. So that was just very informative for me and fun to get to play that other role and get to provide those publication opportunities that I was starting to get a little bit and see the flip side of it.

Q: How was the process of getting this book published?

Johnson: Long. So I actually had my book launch reading [March 23], which was amazing, and I shared with the crowd there that I was wearing a dress that I had purchased for the purpose of wearing at my book launch after I got my first big publication and signed with an agent and I thought, ‘This is the beginning of my author life and I’m going to get a book deal eminently and then my book will come out and I’ll make a million dollars.’ That was about nine years ago that I purchased that dress.

Ultimately, I ended up finding a great home at a very small press, which was on a little different level than I was initially, in my delusions of grandeur, looking for, but it ended up being a really great fit. I had really personal hands-on work with the publisher. I had a lot of say in what the cover design looked like, even down to the fonts that were used in the design of the book.

Q: Your book was recently on the cover of Penthouse magazine, how did that happen?

Johnson: That was a very interesting and pleasant surprise. Over my decade-plus now of being in the writing and publishing industry, I have built up a great network of people who support each other. I think that’s really important, and that’s one thing that Emerson does really well is build that community of writers and readers.

When my book was coming out, I reached out to a bunch of those folks, my trusted readers who I appreciate for their writing and the way that they engage with literature, and asked if they would be interested in getting a review copy, no obligations to do anything with it, but I just wanted to give them the opportunity to get a sneak peek. The woman who wrote that Penthouse piece, Teresa Fazio, is a fellow writer and fellow veteran, she’s a Marine veteran. She enjoyed the book and wrote a piece about it and pitched it to Penthouse. I think she was as surprised as I was to see it wind up on the cover, so that was pretty exciting. I keep joking that now my husband can brag to all his friends that his wife is featured on the cover of Penthouse. My dad was like, ‘I need to go buy a copy of Penthouse magazine for the first time in my life.’ It’s a national publication, so that in and of itself is huge. I can’t say I’m an avid reader of Penthouse, but clearly a lot of people are, and it’s pretty exciting to get to reach that whole different kind of audience.

Q: Can you talk about growing up with your mom in the military and did you ever think that you would join one day?

Johnson: That’s actually something that I explore a lot in the book. Reflecting back on my experience growing up with a mother who served – and she was a reservist in the Army, so we didn’t bounce around to different bases all the time, she was a part-time soldier – two weeks a month, one weekend a year was kind of our general interaction with the military. Then she got called up off reserve duty pretty suddenly to deploy in support of the first Gulf War, Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm back in 1990.

I was 7 at the time, and it obviously was traumatizing to have my mom just snatched away, and another big difference between then and now with the military is that there was a lot of unpredictability surrounding deployments. Now, and even at the time I was in the military, you knew how long you were going to be gone for the most part and it was planned out like, ‘I know my deployment cycle is coming up in four months, so I have to be ready for that.’ That wasn’t the case in the ‘90s. She had orders for an undetermined length of up to two years, so just a ton of uncertainty. She thought that it might be a suicide mission because of the threat of chemical weapons coming into play in the war. I didn’t know that as a 7-year old, but just a lot of terrifying uncertainty.

So with all of that in my background, and being so profoundly affected by my mom’s deployment, why then did I volunteer to join the military and then volunteer to deploy myself? That was a question I was exploring through writing the book. It wasn’t one individual thing that pushed me onto that trajectory. It was a combination of factors. Having a mother who I revered, and I thought of her as my person and my hero, and then she deployed and that kind of reinforced that. I thought, how cool that my mom isn’t just my mom, she’s also a soldier and a healer, and she’s going to a foreign country to help people get their freedom against a bad man. When she came back the public felt that way too, there was a huge swell of patriotism and she was revered, everyone who served in Desert Storm was revered as heroes. So that was kind of what built up in my mind as what it means to be in the military and what it means to be at war.

Fast-forward a few years to 9/11 and the immediate swell of patriotism that happened right after the terrorist attacks felt to me very similar to that patriotic feel around when my mom deployed. It was this very powerful convergence in me, and it kind of awakened this part of me that wanted to follow in my mom’s footsteps and in the footsteps of my grandfathers. And then add in a scholarship to my dream school on the California beach, and the fact that it was four years as a college student where I was basically just taking military classes as part of Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) it just felt like there was this big buffer between me and the realities of the military. No one expected us to be fighting not just one, but two wars when I was done with my college and actually entered as an officer in the military. It was a conscious decision, but it was also a decision that was very much detached from the potential repercussions of that decision in a lot of ways.

Q: What made you get into public affairs in the military?

Johnson: I was a public affairs officer, which was basically the military PR, and I had no idea what that job entailed when I started ROTC. Part of the goal of ROTC is to train you to be an officer in the military and find whatever career track makes the most sense for you. I was an English major, I always loved to write, so I was really attracted to the journalism component of public affairs. That’s one of the pillars of what that job included, there were media relations and internal relations, which involved spreading the word outside of the base and spreading the word inside of the base, informing the 8,000-[person] community. A lot of that involved writing press releases and news articles and I was really drawn to that. There were a lot of other things, like the very formulaic news writing, that I was not prepared for, and that level of censorship that comes into play for obvious, necessary reasons, like protecting security and privacy. But it’s very different from creative writing in that I wasn’t expressing how I felt about things. I was expressing the military’s perspective about things and the key messages that the military wanted out there.

Q: And how does that relate to the title of your book, The Fine Art of Camouflage?

Johnson: The more I wrote, the more I realized that the story I wanted to share, and the many pieces of me that are in this book, is about stories and communication and all of the different competing messages that we’re fed: from ourselves, telling ourselves the stories of who we want to be and building up this persona, stories from other people, telling us who they want us to be or who they think we are, and hearing stories from our families.

My family had this big military family lore, and everyone has elements like that when you’re learning about your history and hearing those kinds of stories growing up. With the military in particular, we see so many stories in the media and in Hollywood that show a very specific and tiny little window into what that actually means. Now we have social media, which I’m grateful was not a huge component when I was a young person. But all of these things just get cobbled together into this view that we have that we take into our life of how we view ourselves and how we view the world. The Fine Art of Camouflage was a play on camouflage in the military, which is obviously a tool for blending in and removing individuality and making you part of a greater whole, and I know that I have done that throughout my life and that most people do that. We shape ourselves into what other people want us to be or what we want ourselves to be and try to be many different things to many different people, so that’s kind of where the camouflage comes into play.

Q: After leaving the military, how was your adjustment back to your regular life and can you explain “moral injury”?

Johnson: Moral injury actually started before I got out of the military and in reflecting, it actually began while I was in Afghanistan. So, moral injury is a relatively new term that has really come to be part of the conversation in the last 10 years or so, not just around the military, but also around healthcare workers, for example. It refers to not a physical injury and not the kind of psychological injury that we traditionally think of with traumatic events causing post-traumatic stress disorder and things like that, but an injury of the soul.

So, I have done something that I feel goes into conflict with my morals and that kind of undermines who I believe myself to be as a person. My job in Afghanistan was essentially to be the information filter between what I saw happening on the ground and what the American and international publics, as well as the Afghan publics, were hearing about that. I was shaping the story in the ways that the military wanted it to be shaped, which I very quickly realized was not a full picture. I understand the role of public relations [is] to put a positive spin on things, but it’s not like I was in charge of selling toothpaste or used cars, we’re talking about huge political and economic efforts, and American lives and Afghan lives. To be playing a role where I was influencing how people felt about that and trying to build support for this effort, that, once I was in the midst of it, I was questioning whether it was a good thing or whether it was being done in the right way. It just felt very kind of sleazy in a way, so I got very uncomfortable very quickly and that built throughout the deployment.

When I got back and tried to resume my ‘normal life’ I just was floundering. I didn’t know how I felt about anything anymore. I felt like the rug had been pulled out from under me. I was on this special operations base where people were deploying every couple [of] months, and literally, I would sit in my air-conditioned public affairs office, watching outside my window as the special forces soldiers ran in the heat of the day in Florida carrying logs, and there was just so much guilt. That’s how my moral injury manifested; it was in guilt. I was relatively safe. I thankfully did not experience sexual assault, I was not directly involved in combat, I didn’t have any friends who were killed, I myself wasn’t injured, so why am I struggling with this? No one around me seems to struggle, my mom didn’t seem to struggle when she got home. The guilt component was really the big thing for me.

Categories