Walker on Writing Essays, Receiving Rejection, and Looking for Humor Everywhere

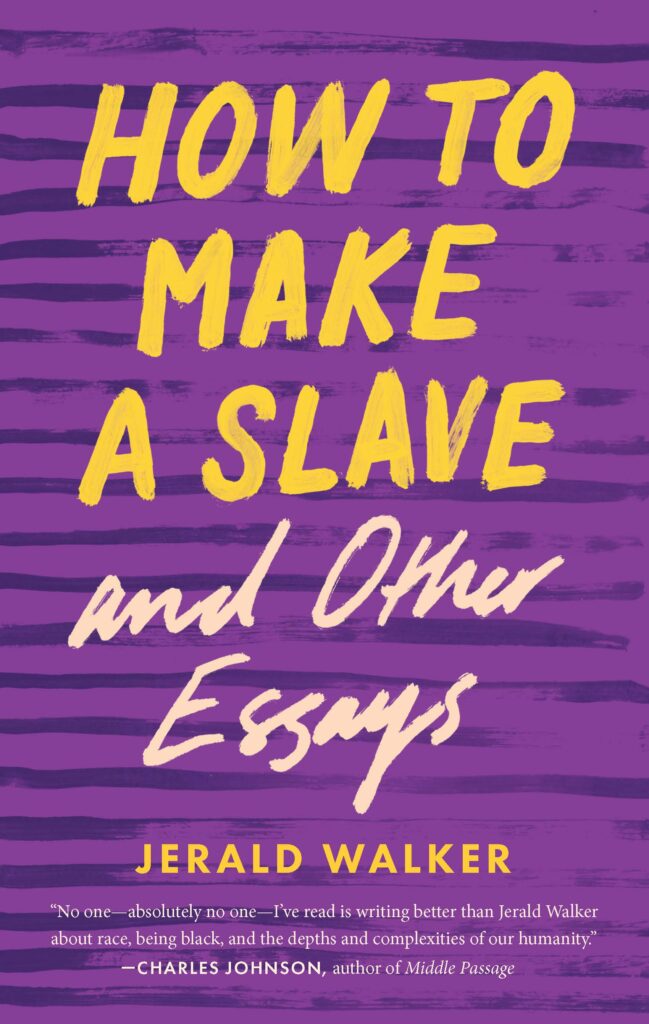

Writing, Literature and Publishing Professor Jerald Walker’s latest book, How to Make a Slave and Other Essays (Mad Creek Books/The Ohio University Press, 2020) is being heaped with accolades, from being shortlisted for a National Book Award to securing Walker an interview with Terry Gross, host of NPR’s Fresh Air.

We asked Walker about some of his choices in writing the book, as well as the response its generated.

ET: Did you set out to write a collection of essays, or did a number of essays you wrote and the ideas they contain coalesce themselves into a book?

JW: I wrote the essays separately with no immediate plan of collecting them for a book. The oldest essay was published in 2006, the most recent in 2020. When I began compiling them, it became clear that of the 23 pieces I had, 14 worked really well together. So I wrote a few more with the intention of echoing various themes and topics to shore up the narrative arc.

ET: The book is dedicated to James Alan McPherson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning essayist with whom you studied at the Iowa Writers Workshop. He eviscerated the first essay you wrote, telling you that you can use stereotypes to lure readers into the story, but once there, you need to show them yourself. How to Make a Slave is comprised of essay after essay that does exactly that. Is “moving beyond the stereotypes” something that becomes easier with time and life experience, or is it something you still work at?

JW: Once you adopt a certain worldview and have a clear sense of your artistic aims, remaining consistent is second nature. I think that’s why—and this goes back to your first question—the pieces coalesced without much deliberate effort on my part.

ET: I could be reading an essay in this book about something so dark or heavy – racism, poverty, health crises – and suddenly come upon a line that made me crack up laughing. How does humor figure into your work?

JW: It’s central to my work, as it’s central to my being. I’m quick to laugh, and I’m always looking for the humor in any situation, even where it’s least apparent. Maybe especially where it’s least apparent. Also, because the topic of race generally causes people anxiety, a little humor often calms the nerves.

ET: Several of the essays are written in the second person. What prompts that choice?

JW: After Barack Obama’s first election, a friend asked me if America was now post-racial. I told him heck no, but that I knew how we could be, and I set out to write a how-to essay explaining the path forward. In fact, the working title of the essay was “How to Be Post-Racial.” As is the case with most of my essays, one thought led to another so that by the time I finished, the original idea was nowhere in sight. The new title was “How to Make a Slave,” and all that really survived from the original idea was the second person narration. But I very much enjoyed working what the point of view, particularly because it can help place the reader in my shoes, which is to say the “you” is both the reader and me. So I wrote a few more second person pieces, and, as luck would have it, I ended up with just enough for one to turn up every fifth essay in the collection, giving the book added cohesion.

ET: Naturally, your sons play a central role in many, if not most of your essays, either explicitly or implicitly. Have they read the book? Have you talked about it with them?

JW: No, my sons haven’t read any of my books or essays. They have zero interest in them, even though they knowthey’re central figures in the collection. My wife says it’s just children being children, meaning they find their father an uninteresting dork, but that one day they’ll come around and devour all of my work. We’ll see.

ET: In addition to being short-listed for a National Book Award, How to Make a Slave landed on The New York Times’s recommended reads list last month. Did you expect this kind of response to the book?

JW: When I assembled the collection, I had high hopes for that kind of critical reception (don’t all writers?), but after more than 20 rejections of the manuscript, that dream dissolved. I came to believe the book wouldn’t even be published. In fact, my agent, even though she loved it, suggested I put it aside and work on something new.

I agreed, but one day, on a whim, I sent it to someone I know who was an editor of the 21st Century Essays series at The Ohio State University Press, and he passed it along to the editor of their imprint, Mad Creek Books. The editor immediately made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. In other words, she said, “I’ll take it.”

ET: What’s something you learned about yourself while writing this book?

JW: Less learned than confirmed. I love writing essays and I’ll never stop writing them, even if there are 20 rejections waiting at the other end of my next collection. Besides, it only takes one yes for good things to follow.

Categories