No Debating It: Exhibit Explores Emerson’s History of Prison Education

By Erin Clossey

One evening in 1959, Jan D’Arcy turned down a date with a Harvard man by explaining she needed to go to prison.

The would-be paramour didn’t believe her and that was the end of that relationship, but D’Arcy ’60 wasn’t lying. As a member of Emerson’s highly competitive forensics team, D’Arcy had an appointment to debate incarcerated men at Norfolk (Mass.) Prison on whether or not rock and roll was a bad influence on society.

The contest – between co-ed college students and men serving prison sentences — was notable enough to have made the front page of publications such as Variety and The Daily Worker, D’Arcy recalled in an email.

“We lost the rock and roll debate,” she wrote.

Over the past few years, Emerson has developed a robust and cutting edge prison education program, offering Emerson BAs to men incarcerated at Massachusetts Correctional Institute-Concord through a program that mirrors as closely as possible the rigor and requirements of a traditional Emerson degree.

But nearly 70 years before the Emerson Prison Initiative (EPI) launched, the College was facilitating the exchange of ideas inside prison through its award-winning debate team. This through line in Emerson’s mission is being explored through an exhibit currently on display in the Iwasaki Library, Disrupting Mass Incarceration: Six Decades of Emerson Prison Education.

“Whether its faculty or students, Emersonians are always looking for new spaces where they can expand dialogues and say something,” said Mneesha Gellman, associate professor of political science and director of the Emerson Prison Initiative. “I think there is potential for many different institutions to engage in this work, but Emerson has done it because there is a specific willingness to innovate and take risks.”

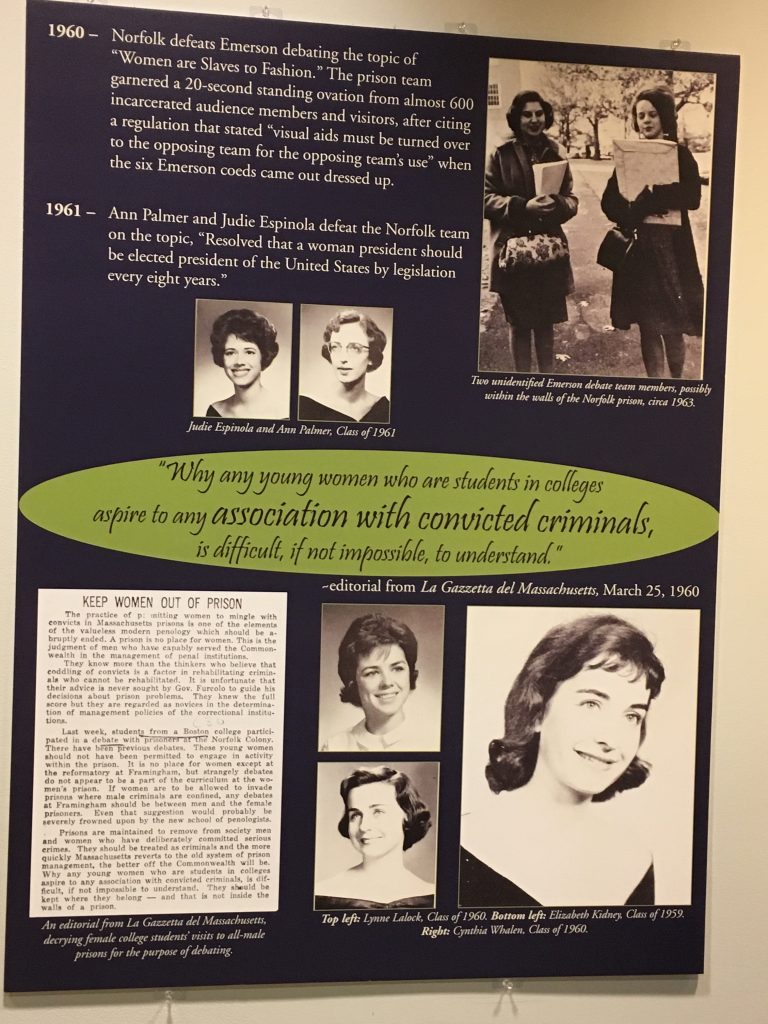

From the early 1950s to the late 1970s, Emerson’s debate team would regularly go up against a team based at Norfolk Prison. Professors Coleman Bender and Haig Der Marderosian ’54, MSSp ’56 coached both the College’s forensics team and their sometime competitors at Norfolk.

“It’s always interesting to me that they were coaching both teams,” said Head of Archives and Special Collections Jenn Williams, one of the curators of the exhibit.

Williams said she didn’t have the Emerson team’s win-loss record during the time of the Norfolk program, but the Norfolk team went 268-6 over close to 20 years of debating university teams from Emerson, Harvard, MIT, and even colleges abroad, under Bender and Der Marderosian.

“Their reputation become so large that they had other schools asking, ‘Please, we want to debate your team,’” Williams said. “They could pick and choose who they wanted to debate.”

The Norfolk team enjoyed great success under their Emerson coaches, but the program actually dated back to the 1930s. Malcolm X credited his time on the Norfolk debate team in the ‘40s (before Emerson’s involvement) with changing his life.

Norfolk Prison was at one time an institution, like Emerson, that looked to disrupt the status quo.

It was designed as a progressive “city behind a wall,” that aimed to replicate as closely as possible structures and conventions of life on the outside, said Tina Dent, assistant director of teaching and learning at the Iwasaki Library, who worked with Williams and Gellman on the exhibit.

Incarcerated men were elected to a sort of “town council,” where they were able to make decisions and give feedback on small matters of day-to-day life at the prison, Dent said. The idea was to rehabilitate the men and prepare them for life post-release, and teaching them to research topics, engage with ideas, and express themselves by participating on a debate team was all of a piece with the prison’s goals.

The community governance aspect of Norfolk Prison didn’t survive much past World War II, and it soon reverted to a more traditional penitentiary. But Norfolk’s commitment to education and communication lasted through the 1970s with the collaboration of Emerson College faculty and students.

“It’s just a really fascinating look at Emerson’s history and how, in a lot of ways, people in the Emerson community think of Emerson as being pretty progressive and forward-looking right now, but I think it has a history of being that way,” Dent said of Disrupting Mass Incarceration. “They were doing what Emerson has always been passionate about, which is social justice.”

Neither Williams nor Dent could determine exactly why the Norfolk Debate Team ended, but they guessed it had to do with the retirement of Coleman Bender. Nearly 40 years after the last Emerson-Norfolk debate, however, Emerson has taken up the mantle of prison education innovator again, this time at MCI-Concord.

Emerson wasn’t the first college to offer classes inside prisons. EPI was modeled on the Bard Prison Initiative, which Gellman was involved with as an undergraduate, and which is the subject of a recent PBS documentary produced by Ken Burns – College Behind Bars, which is available to stream on pbs.org.

But while most college in prison programs offer associate’s degrees from local community colleges, if they offer degrees at all, Emerson is one of the few that confers its own bachelor’s degrees. The first graduates of the program are expected to receive their BAs in Media, Literature and Culture in summer 2022.

After falling into dormancy for many years, Emerson’s forensics team is itself going through a bit of a renaissance, winning a national title last spring against hundreds of college students. Assistant Professor and Forensics Director Deion Hawkins brought some of his students to the opening reception of Disrupting Mass Incarceration last month to demonstrate the art of debate, selecting the topic “Should education be a human right, even for those in prison?”.

Gellman said EPI is “super interested” in bringing debate back into the educational mix at Concord.

“It’s important to remember that what we are doing through EPI, and any prison program, we are challenging the social hierarchies in society by changing who we believe should have access to these privileged educational spaces,” Gellman said. “[President] Lee Pelton is willing to be a thought leader around what it means to disrupt social hierarchies that embed injustices.”

Disrupting Mass Incarceration is on display on the third floor of the Iwasaki Library.

Categories