Laughing Through Catastrophe: How Comedy Can Combat Climate Change

The Man of Steel and Greek mythology’s least regarded clairvoyant took the stage last week to talk about how stories, playfulness, and particularly comedy, can be harnessed to spur action on climate change.

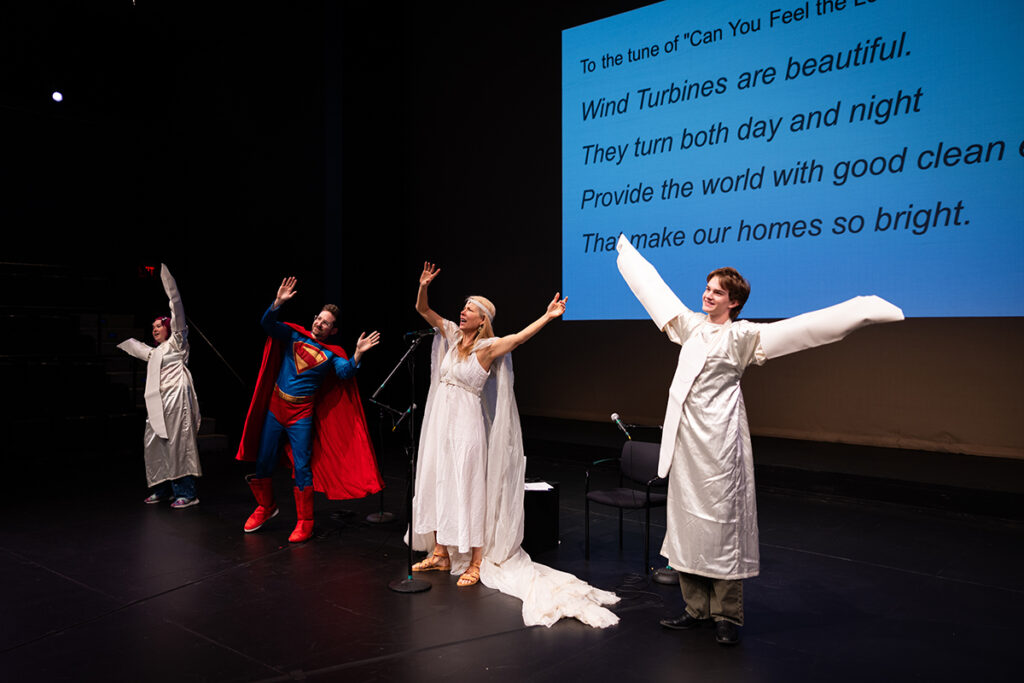

Superman – known on his home planet of Krypton as Kal-El, and known to the Emerson community as Assistant Professor of Comedic Studies Matt McMahan – and Cassandra, a/k/a Beth Osnes-Stoedefalke, a professor of theatre at the University of Colorado Boulder who studies performance and creative climate communication, were chatting in costume for the keynote of Emerson’s annual Teach-In on Sustainability.

“The data is in. Our social scientist friends who study effective climate communication tell us that stories are much more effective than facts for communicating [about] climate,” Osnes-Stoedefalke said.

Kal-El/Superman and Cassandra are apt characters to discuss the power of stories to address climate change. According to ancient myth, Cassandra was given the gift of prophecy by her sometime lover, Apollo, who, when she finally spurned him, cursed her by ensuring that no one would ever believe her predictions. Climate scientists likely can relate.

In the 1990s animated version of the Superman story that McMahan chose to reference, Krypton destroys itself because it becomes reliant on Brainiac, the planet’s version of artificial intelligence, which depletes it of all its energy and resources.

What’s with the get-up?

McMahan and Osnes-Stoedefalke came dressed in costume to demonstrate the power of playfulness in communicating messages.

“Fun is a very silly word, but a highly productive state,” Osnes-Stoedefalke said. “When you are having fun, you’re paying attention, you are alert, you are listening, usually your body is awake and energized. And we need to have fun in this playful state in order to take on a topic that is so dire in nature and so full of this impending doom.”

Costumes also “create images and… attract attention,” McMahan added.

“We live in an … attention economy, and those who control your attention control policy, control discourse, control what people talk about, control what people care about,” he said.

Are myths our Kryptonite?

We use mythological characters to understand ourselves and human nature, and sometimes we can get stuck thinking that a particular myth or story is predictive of how things will be in reality, Osnes-Stoedefalke said.

“We start to think there’s a kind of narrative necessity to what’s occurring right now, because it may have occurred in the past,” she said. “I would just say we can debunk these narrative necessities, that we can write a different story.”

McMahan said he believes that American’s love for superheroes is related to our national obsession with individualism.

“We like the idea of singular heroes swooping in, saving the day,” McMahan said. But the graphic novelist Alan Moore called superheroes a “cultural catastrophe,” and our fascination with them a precursor to fascism.

So should we just toss these myths away?

Myths are already a part of our culture and psyche, and we already have strong connections to them, Osnes-Stoedefalke said, so why not try to “remix” them into something that can shake up worn tropes and bad assumptions?

“When we disrupt these narratives, [and] once we add comedy into these stories, then we have real opportunity to disrupt them in ways that we can really open up possibilities for happy endings,” she said.

What’s so funny about climate crisis?

Comedy can do a number of things, McMahan said: bring people together or push them apart, educate, inspire, persuade, shame, all of the above. It also fosters resilience.

“You teach people to embrace the things they’re scared the most of, and you teach people that comedy can actually bond you together by expressing those emotions in a different register,” he said.

Osnes-Stoedefalke, whose class researches and writes material for professional comics for a Climate Week comedy show in New York, presented a monologue she wrote for the event in which she makes the case for climate comedy.

“We’re in a new ecology now where we distrust government and traditional media, and comedians are emerging as legitimate sources for news and thought leadership. Or more simply put, we are now taking our comedians seriously and politicians as a joke,” she said.

In a tragedy, it’s “too late to save the day,” but in a comedy, “some often preposterous idea is put into action and it turns the table around these human-caused results, and … we get a happy ending,” she continued. “[C]limate comedy is a preposterous idea that might just liberate us through that strange involuntary opening of the mouth and the mind known as laughter.”

That’s great, but how?

An audience member asked McMahan and Osnes-Stoedefalke how comedy and stories can be put into action around climate change.

Last Week Tonight with John Oliver is a good example of comedy in service of action, McMahan said. Oliver often ends his show with a call to viewers to join some kind of stunt or act of trolling-as-activism.

“So, the message of the show lives beyond the show. It’s just giving people one thing to do afterwards, just one thing. And if it’s a fun thing – a funny thing – all the better, because then they’ll want to be part of that,” he said.

But there are more, and often more effective, ways to turn comedy into action than trolling and satire, said Osnes-Stoedefalke, who wrote an article on the topic for the journal Comedy Studies called “Good Natured Climate Comedy.”

Satire is always at someone’s expense, and works to expose their weakness or ineptitude. “Good-natured” comedy looks for shared humanity in our foibles and asks us to laugh — and think — about them collectively.

“I wonder what’s accomplished when people are made to be afraid or ashamed. They make some of their worst choices,” she said. “Sometimes we need the whole range [of comedy styles], but I’m interested in exploring these other forms of comedy to see what kind of impact our comedy is really creating.”

Categories