CSD Students Help Robbins Center Clients Find Their Voices

At the age of 29, Jayme Kelly suffered a stroke that left her unable to speak for a week and a half.

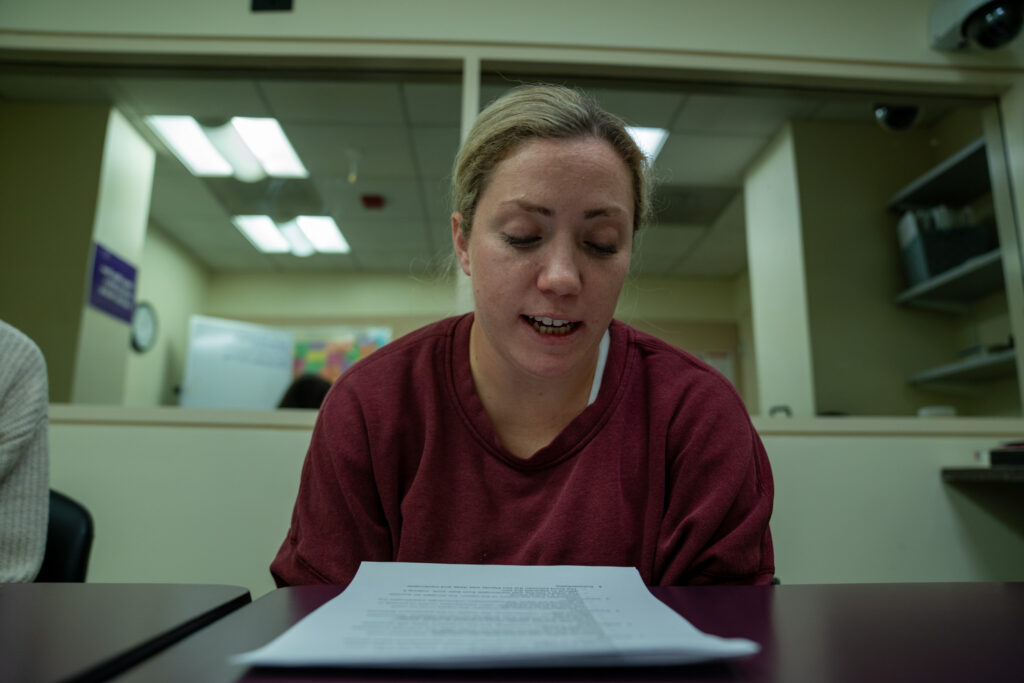

“By the time I got out of Spaulding Rehab [after two weeks] I could say, ‘I love you,’ ‘How are you?’ and ‘My name is Jayme Kelly.’ That’s all I could say for a month,” she said.

But talk to Kelly today and you’d never know she lives with aphasia, a disorder caused by damage to the part of the brain that controls language.

Six months after her stroke, Kelly, now 34, became a client of the Robbins Center, the on campus clinical training facility associated with Emerson College’s Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders (CSD), which trains students to become speech-language pathologists. Every semester since, Kelly has worked with different clinical instructors and CSD graduate students in individual and group therapy sessions.

“The students are so great. They have helped me a lot. It’s better to have a [Clinical Instructor] there also because they can work together,” said Kelly. “The professor knows me, and if the student is having trouble, they can say, ‘For me, I do this and it helps.’”

This fall, Kelly has been working with graduate student Grace Flanagan, MS ‘26, who is being supervised by Clinical Instructor Jocelyne Léger. Léger has 20 years of experience working with children and adults in inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation settings.

In a recent group therapy session, Kelly and fellow stroke survivor Gary Schwab played a version of the board game Battleship created by CSD students. The duo laughed as they propped up folders so they couldn’t see each other’s game grid showing where they had placed their ships.

“I’m not going to let you see!” teased Kelly, who was a nurse at Boston Children’s Hospital pre-stroke, and now works as an in-home nurse with a child with cerebral palsy. “Last time was so unfair.”

But there was one important distinction between their game and the real Battleship, in which players call out coordinates consisting of one letter and one number. Kelly and Schwab were using a grid specially made by Flanagan that uses longer strings of letters and numbers, which adds to the challenge and is a good exercise for their recovery.

“Let’s do zero, two, o, t, six,” said Kelly, which Schwab asked her to repeat, at the same time Flanagan and Carly Drusedum, MS ’26, who works with Schwab, took notes.

Behind The Mirror

As the “sea battle” raged on, Léger observed from behind a one-way mirror, taking notes to provide feedback to her students. Léger feels strongly about the importance of feedback for her students, particularly at the start of semesters.

“I highlight things they’ve done well, like a great way they cued the client,” said Léger. “Or something they could do better. I might say, ‘You know, when this situation happened, this might be a different way to cue them.’ Or [I suggest] ways to modify activities to meet the client’s needs and discuss it during our supervision meeting.”

Cueing, or prompting, a client is important because it supports the client’s word retrieval, instead of just giving them the answer.

Léger said students are often focused on their own accuracy, and might miss an observation when writing notes, like if a client is mouthing silently to help retrieve words.

“Sometimes I’ll also make observations about the clients, because as new clinicians we don’t expect them to see everything,” said Léger.

Kelly has sometimes written letters in the air when trying to elicit a verbal response, and that’s a good thing, explained Léger.

“Whatever you can do to prevent a communication breakdown [is good]. The overall goal is to have them being as effective a communicator as possible,” said Léger. “How they communicate doesn’t really matter. It’s the message intended to be conveyed and being conveyed.”

Robbins Experience Draws CSD Students

Flanagan said she applied to Emerson’s CSD program because of the reputation of its faculty, as well as the clinical experience afforded by the Robbins Center, which works with clients young and old who are seeking help with a variety of language issues. Throughout the past semester, Flanagan was working with a tweener, in addition to Kelly.

“I like that we work with a lot of different populations,” said Flanagan. “It’s interesting and keeps you on your feet.”

The Battleship game is part of the “Language of Letters and Numbers” therapy group. Kelly has participated in other groups, including a book club. Clients can choose the kind of therapy that fits their personality and goals.

“[Jayme] said in the beginning of the semester she wanted to work on correcting errors in her writing,” said Flanagan. “She wanted to work on consonant sounds that are tough to pronounce.”

The hands-on experience with clients and clinicians is invaluable, said Flanagan, who eventually wants to work with children with autism. She said she appreciates that clinicians give more intensive help in the beginning of the semester, and then pull back as the semester goes on, fostering student independence.

“Knowing [Léger’s] behind the mirror is great,” Flanagan said. “I learn from her by seeing how she interacts with clients, [how she] words things, and comes up with new ideas and thinks about clients’ needs.”

With a semester under their belt, Léger said students are really thinking clinically, and don’t need her as much.

“It’s great when you work with a client and student in their first semester, like Grace and Jayme, and get to work with that student in their last semester, and see the differences in their clinical abilities,” said Léger. “It’s very rewarding and exciting.”

Recordings are Reminders

Sessions may be recorded for students and clinicians to review in their weekly one-on-ones to discuss clients’ treatment. For Kelly, seeing footage of herself from 2019 shows her how far she’s come. Back then, her mother had to drive her to the Robbins Center; now, Kelly drives herself.

“Stroke recovery is so hard, sometimes as a stroke survivor you don’t see what you have recovered. Sometimes I get hard on myself. I want to be back [to] where I was before the stroke. Looking at the video, I see I have come so far,” said Kelly.

Kelly has no plans to stop working with CSD students and clinicians at the Robbins Center. At the end of their last group session of the semester, Flanagan asked Kelly and Schwab for feedback about what activities worked and didn’t work for them. She also asked if there is anything they’d like to try next semester.

“It’s really wrapping our work up, but also preparing [the client] and the next clinician for the next semester, so they can go in prepared and know what the client wants to work on,” said Flanagan.

Flanagan said she has learned a lot about what it’s like to struggle with aphasia. Hearing about clients’ challenges and focusing on their speech goals was instructive, particularly learning about what’s helpful to them in day-to-day life.

“I feel like it’s really helped me gain foundational knowledge for the job, and actually do the job,” said Flanagan. “They’re really preparing me for next year when I graduate, and I’ll be really confident going into the field [of speech-language pathology].”

Categories