Five Things to Know About Swallowing

As a medical speech language pathologist, Assistant Professor Lindsay Griffin specializes in research and clinical care of a vital function that is often taken for granted or misunderstood.

As told to Melissa Russell

Sometimes inspiration comes from unusual sources.

For Lindsay Griffin, assistant professor of Communication Sciences & Disorders, it was an episode of MTV’s True Life that introduced her to her ultimate field of study.

After earning a bachelor’s in psychology from Lebanon Valley College in Pennsylvania, she wasn’t sure just what she wanted to do professionally. Her parents pushed graduate school, but nothing was lighting the fire in her belly.

Then True Life—which documented the lives of people as they navigated disabilities, addictions, or relationship conflicts—aired an episode about a deaf person working to improve his speech after receiving a cochlear implant. That looked interesting. Griffin began to shadow speech-language pathologists (SLP), one of whom worked with children with autism, but it didn’t feel like the right fit.

But then a second SLP took her to watch a modified barium swallow, which just happened to be on her caseload that day. In this procedure, a patient eats or drinks foods that have been covered with a barium solution so their swallowing mechanism can be scanned and observed on a computer screen, similar to a moving X-ray.

To Griffin, this study of swallowing was both fascinating and disgusting, and she was hooked.

She attended Northeastern University and earned a master’s in Communication Sciences and Disorders. She became a medical SLP, and focused her clinical work on adults with swallowing, language, and/or cognitive communication disorders after incidents such as a stroke or brain injury. Following stints at Spaulding Rehabilitation Center in Salem and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, she left Boston to pursue a PhD in Communication Sciences and Disorders from James Madison University in Virginia, and then accepted a position at Emerson College. Here, she draws on her clinical and research experiences when teaching undergraduate and graduate students in courses about swallowing dysfunction and neurogenic communication disorders.

In her research and as director of Emerson’s EATS Lab, Griffin focuses on the neural mechanisms of normal and disordered swallowing in adults. She studies swallowing rehabilitation using electrical and sensory stimulation, as well as ways to improve swallowing evaluation procedures. Her work has been published in peer-reviewed journals including Dysphagia, American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, and Experimental Brain Research.

Griffin explains that swallowing is a vital function of eating and drinking, but not necessarily for communication. However, because the same mechanisms are involved— the cortical and subcortical structures, the brainstem and the mouth, jaw, and throat—swallowing and swallowing disorders have long been a part of the field of speech pathology, and are studied in Emerson’s CSD programs.

For this installment of our occasional “Five Things to Know” series, Griffin presents five main ideas associated with swallowing and swallowing disorders.

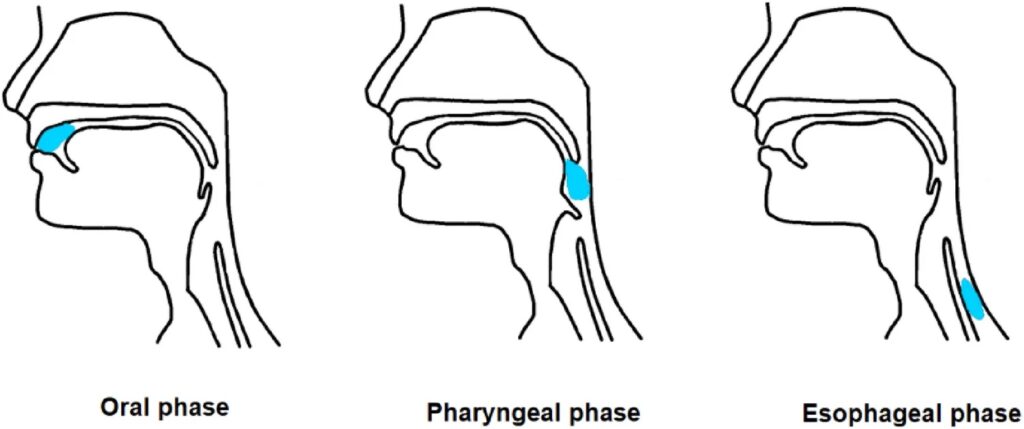

Diagram courtesy of Nature.

Swallowing is vital to eating and drinking, but easily taken for granted.

The three-stage process of swallowing involves voluntary and involuntary phases. First is the oral phase, where the bolus, the soft mass of food that has been broken down by chewing and saliva, is moved by the tongue through the mouth to the oropharynx at the back of the throat. Next comes the pharyngeal phase, where the bolus moves from the oropharynx into the esophagus, and then the esophageal phase, where the bolus is deposited in the stomach for further digestion.

Something could go wrong in any stage of the process.

Damage to muscles or nerves can lead to problems in any of the stages of swallowing. For example, if a person has problems with the tongue muscles, they can have trouble forming a bolus or moving it to the oropharynx. If there are problems in the pharyngeal phase, a food or liquid bolus could move into the airway, impacting lung health and breathing. If the lower esophageal area is impacted, stomach contents could be regurgitated into the esophagus, irritating the lining and causing heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux.

Losing the ability to swallow can be drastically life changing.

Unlike the head and neck cancer patients of past decades, who tended to be older smokers, Griffin sees patients who develop head and neck cancers in their 30s, primarily due to human papilloma virus. They can live for many years post treatment and need to develop compensatory strategies for living with impaired swallowing—such as swallowing with the chin down, or with the head to the side. Consider the embarrassment of eating in a restaurant, with friends or family, and worrying about drawing attention by coughing, sputtering and choking, and having to make maneuvers that may seem ridiculous to others. It can take a lot of effort and time to modify food and drinks to make them manageable for someone with a swallowing disorder, which can diminish any pleasure drawn from cooking, food preparation, or eating.

Swallowing disorders can be invisible.

When people have brain injuries, they are largely invisible, and the person can be perceived as being rude, weird, or impulsive, but it is because of the injury. Swallowing disorders are similarly invisible. There usually isn’t anything obvious to signal someone has that type of disability, but socially, people aren’t able to enjoy the same experiences as someone who doesn’t. This can be especially true around the holidays as folks gather for special meals and traditions. It can be difficult for patients and families to navigate the risks and benefits of eating and drinking when there are safety concerns.

Swallowing disorders are a major concern for end-of-life care.

Nobody wants to talk about what they want the end of their life to look like, but when an illness or dementia has progressed to the point when a patient has stopped eating due to swallowing problems, it is time to consider what is being done to ensure quality of life. The conversation needs to include education about making the process of eating easier for the patient who wants to continue to eat and drink. Are they willing to accept the risks associated with swallowing dysfunction? Can they be made more comfortable? What do they need to protect their dignity while they are trying to live out their best possible life? These are the tough conversations that SLPs can help patients and families to navigate.

Categories