Communication Science & Disorders Students Jump Into Telehealth

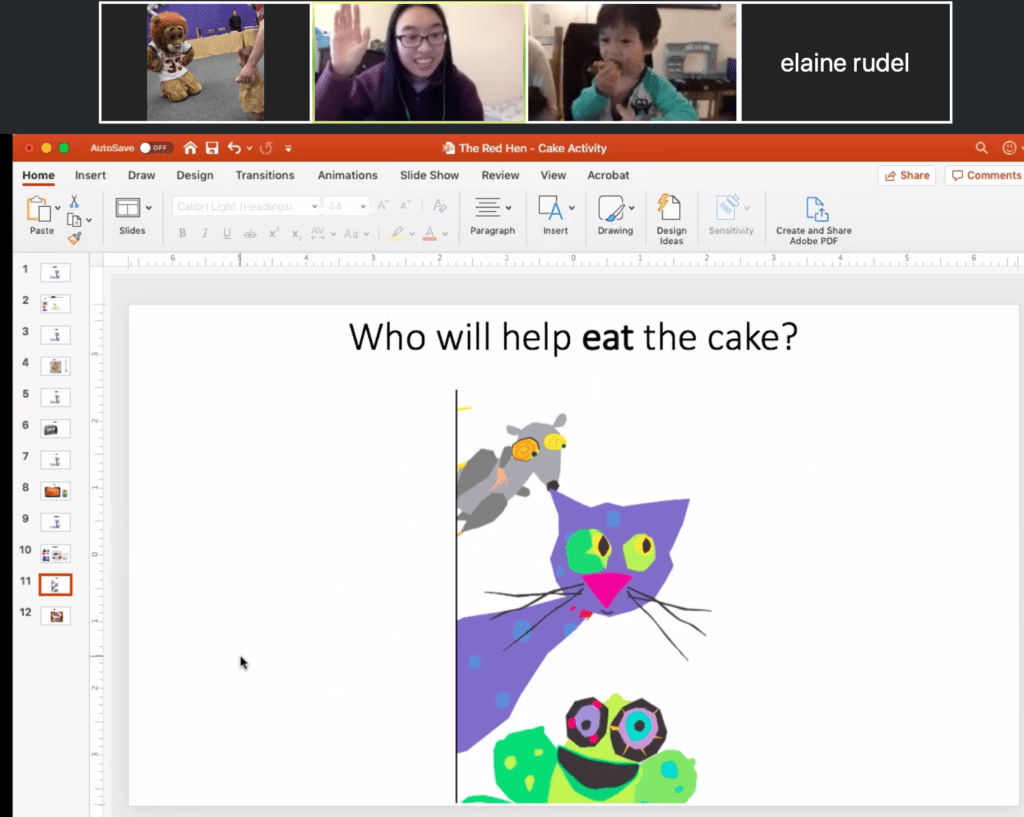

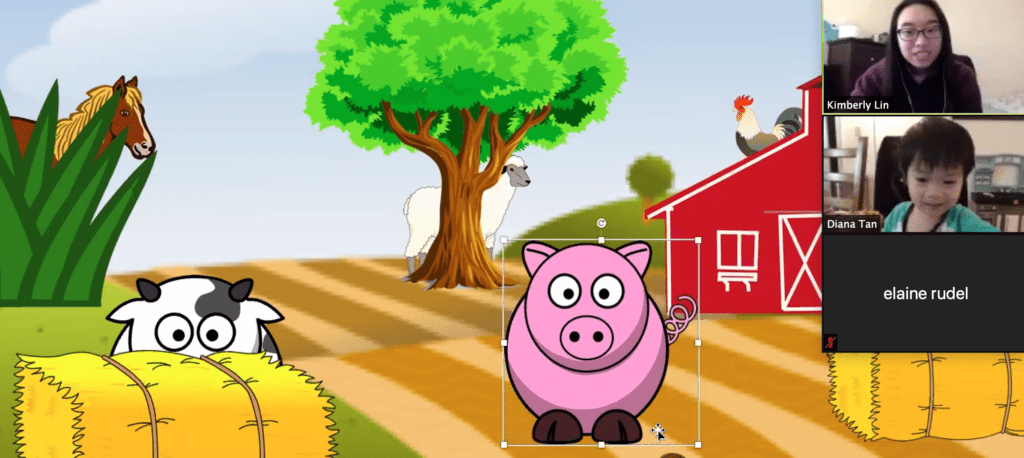

In the beginning of the semester, Kimberly Lin, MS ’20 worked with Liam, her 3-year-old client, in an office. But now she was meets with him in his home. Sort of.

The COVID-19 pandemic pushed most face-to-face interaction online, forcing the Robbins Speech Language and Hearing Center, the clinical training facility for Emerson’s Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, to orchestrate telehealth sessions instead of in-person, one-on-one therapy.

A window into the clients’ homes has its benefits. Sessions take place in their living rooms, kitchens, or bedrooms, so clinicians can see their clients’ daily environments and what they have to work with. And clients can immediately implement what they just learned.

For graduate students like Lin, it’s provided a new learning experience, an especially valuable one as telehealth is expected to become more common in the industry.

In a recent session, Liam, a 3-year-old who was brought to the Robbins Center by his mother, Diane Tan, because he was slightly behind his peers in speech development, was learning how to respond to questions:

Lin: Where should we put the cake?

Liam: Oven!

By utilizing an interactive computer program instead of showing physical pictures as done in a clinic setting, Lin worked with Liam to use appropriate syntax in multiple word utterances.

Lin: What color is the pufferfish?

Liam: He’s orange!

“If you are trying to keep a 2-year-old engaged in an activity, the most efficient way is through parent coaching,” said Lynn Conners, director of clinical programs for the Thayer Lindsley Family-Center Program at the Robbins Center. “That has always been a piece of our style at the Robbins Center, and it has translated quite beautifully to the telepractice model. We’re really using caregivers as the leads in communication intervention with clinicians, and providing them with models of coaching.”

The Robbins Center worked with about 100 clients before the pandemic, and retained 71 percent of them, said Conners. Technology issues prevented the others from continuing to work with the center. Clients are as young as 12 months old, and range into their upper 60s.

A wrinkle generated by the coronavirus stay-at-home guidance is that throughout the entirety of the program, graduate students need to clock 375 clinical hours with the Center’s licensed speech pathologists and clients. Dissolving the program’s toddler group sessions created complications. Students were getting four hours a week, and then just one hour. The young children’s individual sessions got a little longer, and the remaining clinical hours had to be satisfied by a simulation case program.

Clinical instructor Lauren Berry said COVID-19 has really brought out the counseling part of the job, because what the client may need is not solely related to speech, hearing, and language. She’s found herself asking clients how their week went, how are they doing with isolation, do they have enough food, and checking in with their overall well-being.

“Sometimes I glaze over it when we’re in the building. I’ll ask how things are going, and parents will say ‘Fine.’ Now I lean in and ask, ‘Are you fine?’ And they say no, they’re not fine. And we’re providing them space to not be fine. It’s making it O.K. to say you’re struggling. Everyone is struggling.”

The switch has not been without its challenges.

Delaney Mandel, MS ’20 said she’s accustomed to playing with her clients, using toys and games to help kids work on articulating sounds. Telehealth has not only forced Mandel to interact with the children through a screen, it’s also thrown the occasional bit of disruption into the sessions, when Internet connectivity breaks down.

Amelia Parent, MS ’20 said current circumstances have changed her definition of success. In the clinic, they were very data driven, using protocols targeted to get desired results. Now she more often goes with the flow, paying attention to what interests the child on the screen.

Parent said her goal is to give one tangible teaching tool for the parent to take away from each session. That could be something like a strategy for listening and auditory memory skills.

“Even if the entire session is [learning that strategy], we can define that as a success,” said Parent. “’Let’s see if we can practice it and get it X amount of times.’ Data collection is different with teletherapy.”

Being able to interact with both parent and child in their own home setting has advantages when it comes to testing treatment and theories.

Meghan Parlow, MS ’20 said before the teletherapy sessions, they’d have to wait a week for the parent to tell them that something didn’t work at home.

“They’d explain … the circumstance and what they thought. We’d have to brainstorm ways we could do strategies that were more successful and then wait a week,” said Parlow. “Now we’re trying strategies in the home and seeing that it’s not working. We can problem solve right then and change our approach. It’s immediate trial and error.”

Clients have also been pleasantly surprised with the results. Liam’s mother, Diana Tan, has been working with the Robbins Center for four semesters through four graduate students. Initially, she took Liam to the Center because he wasn’t developing speech at the same pace as his peers, and his teachers had also issued concerns.

Tan said she voiced doubts to Elaine Rudel, the licensed pathologist who oversees Lin, about how successful the telehealth sessions would be for her son. She admits there are some goals they’ve been unable to make progress on since social distancing began, but she said that Lin has far exceeded her expectations.

“She has really made the best out of each session, was always prepared with materials, and she has such a calm and confident demeanor,” said Tan. “I’m always surprised that she manages to hold his attention for the whole session – that’s not easy to do!”

For the graduate students, they’ve learned how to adjust their expectations, be flexible, and know that throughout their career they’re going to experience unexpected outcomes and alter their thinking.

“With good partners, the education and communication growth can still continue,” said Conners. “It’s been remarkable. One of my favorite stories was a kiddo being so excited to see the lead teacher in his group, that he was looking around the back of the computer to see if she was there. This is a little kid with an [autism spectrum disorder] diagnosis. He was so excited saying, ‘I want to find you.’ That’s creating a sense of community.”

Categories