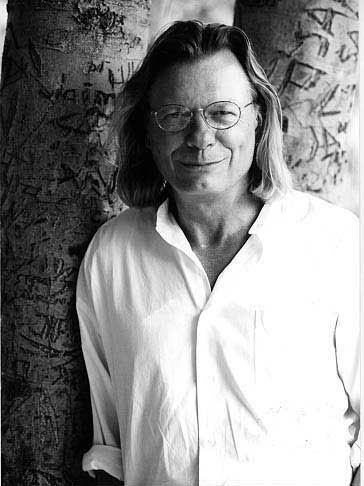

Thomas Lux ’70 a “Robust and Tender” Poet, Teacher

As a poet, Thomas Lux ’70 was a “supporter of all the underdogs,” his verses often infused with the worries of the working class, sometimes with the tang of his father’s dairy farm, said his friend of nearly five decades, Emerson Professor John Skoyles.

As a teacher, Lux was the “opposite of an elitist,” Skoyles said. Whenever they’d go out to dinner, Lux would invite two or three students to tag along, and he shared everything he knew with them, telling them to “read ’til your eyes bleed.”

“He had a great feeling for the common man, the underdog, and the person who was trying to do something,” said Skoyles, professor and associate chair of the Writing, Literature and Publishing Department, who met Lux in graduate school at the University of Iowa and taught alongside him at Sarah Lawrence College.

On February 5, Lux, 70, died at his Atlanta home.

Lux came to Emerson in the late 1960s, when the writing program was still new, his professor, James Randall, said in a 1998 Ploughshares profile of the poet.

“He looked vaguely like a hobo in dress and manner, but he stayed on,” Randall said. “There was a freshness and openness about him, and he spread his enthusiasms to others. Before we knew it, we had a serious poetry group at our college.”

After graduation, Emerson hired him as poet-in-residence. He attended the Writers’ Workshop at Iowa for a year but left before finishing the program to return to teach at Emerson, according to Ploughshares. He taught at Columbia and Oberlin colleges before jumping to Sarah Lawrence in 1975, where he commuted from his home in the Boston area for years. At one point in the mid-’90s, Skoyles was his roommate.

In 2002, he moved to Atlanta to teach poetry and direct the McEver Visiting Writers Program at Georgia Institute of Technology.

Randall published Lux’s first chapbook, The Land Sighted, while he was still an Emerson student, under the imprint Pym-Randall, which went on to publish Lux’s first full volume, Memory’s Handgrenade, in 1972.

He went on to publish more than 20 full volumes and chapbooks, including Split Horizon (1994), which won the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. He was a former Guggenheim Fellow and a recipient of multiple National Endowment for the Arts grants.

Emerson awarded him an honorary doctorate of letters in 2003.

Lux was born in Northampton, Massachusetts, and was raised on a small dairy farm, a circumstance that surfaced in much of his poetry, according to Ploughshares, including “Triptych, Middle Panel Burning.”

It happened that my uncle liked to take my hand in his

and with the other seize

the electric cow fence: a little rural

humor, don’t get me wrong,

no way child abuse…

The man who wrote poems titled “Commercial Leech Farming Today,” “What Montezuma Fed Cortes and His Men,” and “Pecked to Death by Swans” “does not offer bromides or remedies,” wrote poet Stuart Dischell in Ploughshares, “but reminds his readers of humanity’s horror, humor, and heart.”

Lux was a prolific reader of his own work and was known for his powerful and flamboyant style.

“He really declaimed his poems, almost like they were sermons, and they were vaudevillian,” Skoyles said of his readings.

In the 1998 profile, Dischell asked Lux why he thought poetry readings had suddenly become so popular.

“A lot of us feel overwhelmed in our lives by a popular culture dominated by technology, hugely overproduced movies and music,” Lux said. “Poets have only one instrument. There are no backup singers for poets, no props, no synthesizers, no special effects. Just pure lucid words. Put in the proper order—which includes the order of their sounds—they can shake us to our bones.”

Early in his career, Lux started a small press, Barn Dream Press, which published the works of young poets—among them the late Bill Knott, an Emerson professor whose works Lux had edited into a retrospective volume shortly before his death.

It took him years to edit I Am Flying Into Myself, culling Knott’s legacy from 1,500 poems, and Lux called it “the best thing I’ve ever done,” Skoyles said.

Skoyles said he recently read that Lux once said if he could play centerfield for the Red Sox instead of being a poet, he might have done it. His longtime friend said “there’s some truth to that.”

He never forgot where he came from, and constantly worked to make poetry something vital and inclusive for his many students and readers.

“What you remember about Tom was his incredible poetry, but he was an extraordinarily generous person,” said Skoyles. “He was a great teacher, he was a great friend, he was robust and tender at once, and I always thought he was invincible.”

Categories