Flynn’s Doc Tells Story of Film’s Death and Preservation

This summer, Emerson College Visual & Media Arts Assistant Professor Peter Flynn enjoyed promoting his contradictorily-titled documentary Film is Dead, Long Live Film! at more than 30 festivals.

The movie has won three best documentary awards: at the Desertscape International Film Festival in Utah, the New Jersey International Film Festival, and the Indy Film Fest, as well an Audience Choice Award at the Southside Film Festival.

Flynn talked with Emerson Today about his basement smelling like vinegar, why he enters particular festivals, students’ fascination with projectors, and more.

This is an edited version of the conversation.

What was your summer like in terms of your film?

Flynn: Busy. Very busy. It premiered in late March as the semester was winding down. I was traveling and screening the film. I took it to Italy [for the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival]. It’s been great. It’s exhausting. All this traveling. It’s been very rewarding and well received by audiences and critics liked it. [Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival is] a big film festival for archival restoration of films from all over the world and different periods.

It screened at the Indy Film Festival in Indiana and won an award there. Italy, New York, and I went to Utah, Philadelphia, Wisconsin and Canada this month.

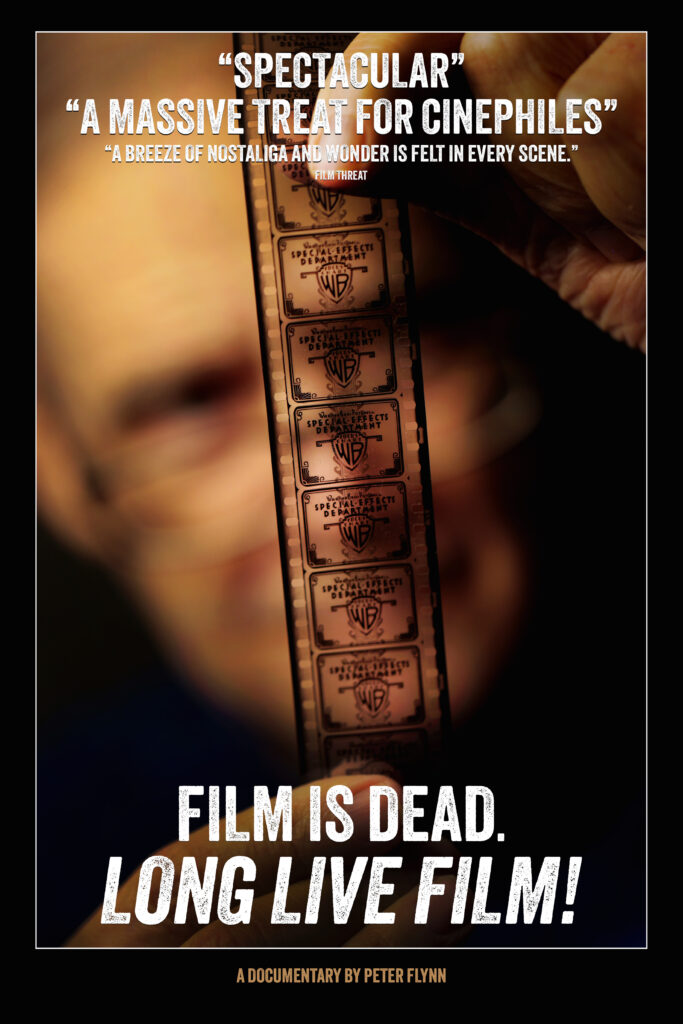

Please explain the title of the film.

Flynn: Film is dead. Film has been replaced by digital. That occurred in the mid- to late -2010s. At current estimate, there are less than 2 percent of theaters that can show film. That figure alone shows that film is pretty much dead as a medium of exhibition….That’s the first half of the film’s title. The second half is people who refuse to let it go and hold onto it and continue to save it and preserve it. For a very small few, film is very much alive, even if in the big picture it’s not.

It’s looking at the last generation of people who interact with photochemical film. Baby Boomers, predominantly. The future of film is finite. This film was an attempt to capture analog cinephilia before it’s really gone.

Did you use film to make it?

Flynn: (Laughs) I shot it on digital. That’s how it goes. To shoot it chemically would be an act of madness, and I simply couldn’t do it.

It’s looking at 1s and 0s, and you take this little piece of plastic of film, and I can scan this. It’s Lumiere film from 1895, and film that is 130 years old. I can capture all this film via scan and run it off a computer, put it on Blu-Ray, and project it onto a screen. Is it the same thing? For audiences, yes. For people who love film, film loses its materiality, and is handled and cared for in a different way [than a digital movie].

We teach filmmaking at Emerson College. We teach analog chemical filmmaking. But our students have no real contact to film outside of that class. It’s not something you handle. It’s not something you store, or it takes up a large portion of living space. Film is something you need to take care of as time goes by. You’ve got to aerate it, or it loses its plasticity. If it’s not stored correctly, film degrades and the image gets lost. For more than 100 years film required certain care and attention, and it no longer does.

Why did you want to make the film?

Flynn: ‘Cause I love film. I love the history of film. This part of film history will be lost very soon, in 20 or 30 years. This culture will be history. These stories will be gone. It hasn’t been recorded. At the 11th hour as everything is winding down, I wanted to capture that culture as much as I could.

What happens to film now?

Flynn: Most film, the vast majority of film, has been thrown away. The people who made it, shot it, released it, never imagined it would have a life beyond its initial run. It was dumped and destroyed, melted down to reclaim the silver and chemicals.

The films that survive are exceptions to the rule. They end up in archives, but also with individuals who saw value in them. They would take care of them and then cast them on to some other generation. But now we’re looking at 50, 60, 70 years of survival, and these films are degrading. If film is not in an archive, it is decaying and deteriorating, and won’t be with us much longer.

I’m 51, I came into film in the video era. Anyone my age or younger has no connection with film. It was video, DVD, and now, streaming. We’re completely disconnected from the materiality of the form we love and dedicated our futures and careers to.

Do you own film?

Flynn: I do. Not a ton, I have a collection. It’s beginning to decay. With film made from 1952 onwards, the chemicals break down and give off a vinegar odor. Go into my basement and it smells like vinegar. It’s decomposing film.

I’ve donated to the Library of Congress. Last year I sent a 100-year-old film to the Library of Congress to have it stored properly. Over the years, I’ve donated a number of rare prints to the Library of Congress, including a strip of film from one of the earliest pioneers, Etienne-Jules Marey, dating back to the late 1880s, and currently the oldest film artifact in the Library’s holdings.

In the last several years, I’ve sent news reels, old 1920s silent eras. A range of trailers from the ’40s to ’50s. A lot of oddities, forgotten films. Some films no one knew existed. That’s the important stuff. The Library of Congress is making a concerted effort to reach out to private collectors to save film, because the life span is so finite and the end is very near.

When did you come up with the idea for the film?

Flynn: I made a documentary [The Dying of the Light] about the demise of analog film production. That was looking at what it’s lost to digital. I talked to the last generation of career projectionists and that culture and what that practice was like in the booth. I realized I had captured the shift to digital, but not what wasn’t being saved with the shift to digital. I wanted to make the other side of the coin.

How’d you find them?

Flynn: Many were projectionists. It was very easy. It’s a small world. You make contact with one and they connect you to another and so on and so forth. Once you gain their trust.

Back in the ’70s into the 1980s, the FBI used to hunt down and prosecute private film collectors. They considered them pirates, buying and selling things owned by studios. Many collectors were arrested, and some went to jail. It created paranoia in the 20th and 21st centuries.

I think now that sense of fear and paranoia about that Disney print in your basement is beginning to fade away. Collectors are more open to talk about this. The great irony is the studios, who they set out to prosecute, put in prison and fine – they now go these collectors for DVD extras or missing soundtrack or trailers or deleted footage. The situation has changed dramatically from the situation 40 years ago. Now collectors are seen as saviors.

How does this summer’s experience help you be a better educator for Emerson students?

Flynn: You have to justify your presence in the classroom. Justify it by showing you know what to talk about. It’s not just facts and figures, it’s about knowing the experience. It’s important for me that if I’m teaching filmmakers, I talk to them as one filmmaker to another.

I know the pains, the neurosis that goes into this and often blocks you. And I know the way out of those traps, and that I can speak to them from earned personal experience. That’s the primary reason. I’m fundamentally a teacher. Filmmaking is little more than a hobby in practical purposes for me.

What would you ask yourself?

Flynn: It’s important that students are understanding history. One class teaches 16mm film production. Students in VMA have limited opportunities to engage with chemical films. It’s a tremendous experience because they can dip their toes into the water that generations of filmmakers have been bathing in. They get a sense of how films were made for 100 years, cut, that you had to send things off to a lab, and wait for it to come back, or the way that film smells from a hot bulb or a projector. Or that anxiety of when it gets stuck in the projector and snags a bit. I think it’s important that we pass some of that on to students today….

When I take out the projector, kids jump up and start recording video of the projector. They take out their phones and take selfies with the projector. They’re amazed that someone put this machine together and devised this whole medium. You don’t know how a laptop works. I just hit a button, and with a projector you can look at the gears, the wheels, and see how film moves and see images of film in light. You see the soundtrack on the edge and see how they did it. The magic is plainly visible. Part of the beauty of film is you see how It works. I could take a strip of film from 1895 and run it in projectors today. Straight out of the gate, the technology was there and that good. In the 1950s, a 10-year-old kid could have a projector in their room and have an image on their wall. In the 1970s, we were using the same technology that Charlie Chaplin was using, and Cecil DeMille in the 1940s.

Categories