Interview: Grossman on the Intersection of Autism and Gender

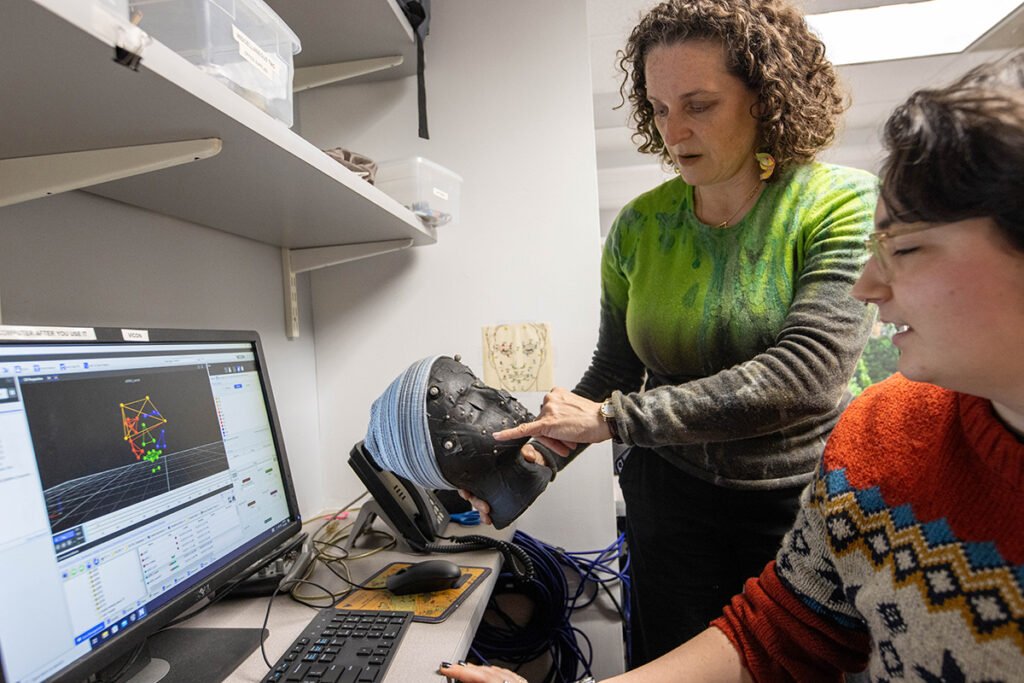

Communication Sciences & Disorders Professor Ruth Grossman has directed Emerson’s FACE Lab since 2008. In her work, Grossman studies how autistic and non-autistic people communicate and how their facial, vocal, and verbal expressions are perceived by others.

This academic year, Grossman is on leave as a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard University, where she is investigating the “Intersectionality of Gender and Autism”. On April 10, she will present some of her findings in an online talk hosted by the Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Emerson Today talked to Grossman about the impact gender has on how autism is diagnosed and perceived, the importance of representation in designing first-impression studies, and the implications of her work for both autistic and neurotypical people. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Emerson Today: When was autism first diagnosed? And where did the assumption that it affects mostly boys come from?

Ruth Grossman: Leo Kanner first described autism in the US in a paper published in 1943 — he coined that term, actually — and most of the case studies he presented were white boys of highly educated, well-to-do families. In part, of course, this is because only highly educated, wealthy families had the knowledge and the resources to consult Dr. Kanner. One year later, Hans Asperger published a paper describing a similar group of boys in Austria. That’s the origin of why autism was conceptualized as a primarily male diagnosis and why there still is a 4:1 boys to girls ratio in autism diagnoses today.

In the last decade, or so, the field has come to realize that maybe we just don’t know what autism looks like in women. It is, after all, a diagnosis of social behavior, and societal expectations for social behavior are different for females than they are for males. It also seems pretty clear at this point that there are some actual behaviors that are different for autistic females compared to males.

ET: Can you give an example?

RG: I was … at the ASHA [American Speech-Language-Hearing Association] Convention [last fall], and one topic that kept coming up was repetitive behaviors and restrictive interest, which are part of the diagnostic criteria for autism. People were talking about the idea that repetitive behaviors of autistic girls may just look different from those of autistic boys. [Many autistic girls] are into ponies and Taylor Swift and makeup or dress-up, activities that are conceptualized as “girly” things, and that non-autistic girls are also into, so they are not raised as a possible reason to pursue a diagnosis of autism. But autistic girls tend to be more intense about these interests than non-autistic girls, which is an important qualitative difference.

I thought that was a very interesting point, because I don’t think it’s so different for boys. Many autistic boys are into trains and mechanical things — a lot of non-autistic boys are into those things, too — but again, there’s an intensity difference. But if you’re using the stereotypical expectations for autism and looking for autistic girls to be into trains, you’re not going to find as many of them.

If you look at adults who are diagnosed as autistic, the gender ratio narrows, it’s more like 2:1 than 4:1, so that gives you an indication that there are a lot of autistic women who are missed as children, but diagnosed as adults, and that maybe that 4:1 ratio was never real.

ET: Do you have an idea why women might get diagnosed later than men?

RG: I think one big piece is the bias that still exists in the medical world that says that this is a diagnosis of males. [T]here is a test called the M-CHAT [Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers]. It’s a screening test that a lot of pediatricians perform. If you get a positive result on the M-CHAT, it means there should be a follow up with a more complete evaluation. A group of researchers looked at the reasons that children with a positive M-CHAT result were not referred for further evaluation, and found that one of the primary reasons was if the child was a girl.

So the pediatrician who sees a kid on an 18-month well visit is more likely to explain away a positive M-CHAT result in a girl as ‘She was just having a bad day,’ or ‘The parents misunderstood something,’ or ‘It’s probably nothing,’ or ‘She’s just shy,’ and not send them for further evaluation, whereas if it’s a boy, they are more likely to say, ‘Oh, well actually, you should follow up on this.’

ET: What does your research look like?

RG: I do a lot of first-impressions research to try and understand how the communicative expressions of autistic and non-autistic adolescents and adults are perceived by others. We show very brief – just a few seconds – video clips of autistic and non-autistic people to others and ask questions that relate to social behavior and inclusiveness. For example: ‘Do you think this person has a lot of friends?’ Or ‘Do you think this person would start a conversation with someone?’ etc.

One of the CSD master’s student who graduated a year ago, Meghan Baer, was interested in adding gender into the mix, so in addition to asking these social questions, we used slider bars for how ‘masculine,’ how ‘feminine,’ how ‘neither/other’ do you think this person is. We showed videos of autistic boys, autistic girls, non-autistic boys, and non-autistic girls, all of whom were cis-gender, to a group of neurotypical adults and collected data on their social and gender perception ratings.

What we found is that the autistic girls were rated less favorably on the social ratings than the autistic boys. Both autistic groups were rated less favorably on the social ratings than the non-autistic kids — that is not surprising and has been the standard finding in this type of research across multiple labs and multiple methods. But the autistic girls were rated even less favorably than the autistic boys. In addition, the autistic girls were rated as less ‘feminine,’ more ‘masculine,’ and more ‘neither/other’ than the non-autistic girls.

We’ve been referring to this as a ‘double penalty’ for being an autistic female. The autistic girls in our videos were perceived as less socially skilled than the autistic boys, and also less feminine than the non-autistic girls, so these autistic girls are not matching the expectations for both neurotype and gender. That’s what prompted me to write the proposal for Radcliffe, and that’s what I’m following up on now.

ET: Where are you in the research?

RG: I am following up on that initial study and working to broaden the representation of gender, as well as race and ethnicity, in the videos we can use for first-impressions ratings. I started soliciting videos of autistic adults from a broad range of backgrounds. So far, more than 40 autistic adults have responded and created videos for this purpose.

There are a few different videos that I’m asking people to create, but the one that is really the heart of this project is a video with the prompt, ‘Tell me your journey to diagnosis. Tell me how the various aspects of your identity relate to your autism diagnosis.’ And some form of ‘Who are your people? What are the communities that you identify with?’ One of our current CSD Master’s students, Cai Conners, is planning a thesis project to look at the themes that emerge in the videos of people who identify as non-binary, agender, or genderqueer. Cai is interested in analyzing people’s narratives of, ‘I am genderqueer and autistic, so in that intersectionality, where do I feel I belong? Who are the people that I actually want to talk to?’ and I’m really excited about what they are going to find with that analysis.

We are actively recruiting more individuals to participate in this project because I want a broader representation of racial, ethnic, and gender identities in the videos. In addition to analyzing the narratives themselves, my goal is to use segments of these videos for first-impressions studies and I want to make sure there will be more than just white, cis-gender people in these videos, which is what a lot of first-impressions literature is based on. We’re trying to connect with affinity groups that will allow us to reach autistic people with broader representation for this set of videos, so we can run a new first-impression study that is more representative of the population as it actually is and explore aspects of intersectionality in how these impressions are formed.

ET: When you recruit the people to watch these videos and give impressions, are you doing the same thing? Are you trying to make that as representative as possible?

RG: Yes, that’s part of the next step. It is important not only to use a diverse group of research participants and get their impressions, but also to understand who these participants are. Because part of the process is going to have to be an in-group vs. out-of-group analysis: ‘What do I, as a cisgender white neurotypical woman perceive about another cisgender white neurotypical woman vs. what do I perceive about a Native American transgender autistic man?’ and vice versa. There are a lot of factors that drive first impressions, including, is this somebody who visibly shares my identity or not?

We’re going to want a lot more information from the research participants who provide the ratings writings than I’ve collected before, so I can better understand that ingroup/outgroup piece. And I’ve started to realize that it is going to take me a lot longer to establish this dataset than I thought, definitely longer than this academic year. So what the students in my lab are focusing on right now is a lot of the outreach and recruiting to as many groups as they can identify across different geographic regions. The other part of this project I’m currently working on is to get a better understanding of the right questions to ask.

ET: What do you mean by the ‘right questions’?

RG: A lot of the questions we’ve been asking in first-impression studies are things like, ‘Do you think this person would start a conversation with someone else?’ But it’s entirely possible that that question is understood very differently from an autistic perspective than a non-autistic perspective. You could say that this is a positive thing, because the person seems to have the communicative capacity to start conversations and that’s good. You could also look at it and say, ‘Oh my God, that person would just start talking to me even if I’m not open to having a conversation, and that’s a horrible thing.’

And it’s not just autism, right? Introvert, extrovert, cultural differences – what are the assumptions that we’re making about what is good about social interactions, and how is that reflected in the questions that we ask? So I am spending time during this leave talking to autistic adults to get their thoughts on what questions are most meaningful to them and how we best frame these questions, so they feel relevant across neurotype and gender. I want to start pilot testing soon and get a better understanding of what makes a good question. So those are the things that we’re spending the spring semester doing.

ET: Who are you working with on this?

RG: Right now in the Face Lab, there are two Emerson undergraduate students and three graduate students, most, but not all, from CSD. There are also two Brandeis students and three Harvard students whom I hired through the Radcliffe Fellowship, as well as one high school student, who has been with the FACE Lab since last summer.

It’s been exciting to have so many students from multiple institutions working on these projects, talking to each other, sharing their perspectives and areas of expertise. I think we’re all benefiting from working with people across a range of different majors and programs. That’s been a lot of fun and a great way to move this work forward.

ET: How much interaction do you have with the other Radcliffe Fellows?

RG: All of us have offices in the same building and we attend talks given by the Fellows twice a week. The goal of this fellowship is to bring people together and have interdisciplinary conversations — just go in with an open mind and see what you can learn from a poet, from a mathematician, from an historian. I’ve been to talks by astrophysicists, filmmakers, anthropologists, biologists, economists, and other fields and it’s been fascinating. This is what the Fellowship staff keep telling us is going to happen, which is that you just get ideas about things that relate to your field from talking to somebody who does something completely and utterly different.

ET: What is your hope for this research? What’s the application that you would love to see it have in the real world?

RG: I’m hoping for greater awareness and understanding across neurotypes. A lot of neurotypical people do not understand what autistic people are trying to signal, just as many autistic people don’t really understand what non-autistic people are trying to signal. This “double empathy” framework is really what my work is living in.

The first thing we do, before we get to have a conversation, is to see somebody coming toward us across the room. That’s when first impressions happen and they are going to dictate what happens next and how that conversation flows. Or whether we are even going to have a conversation at all. I want to raise more awareness and gain more understanding of what the features are that go into forming these first impressions and how these impressions influence what happens next.

Categories