Four EPI Alumni Share Educational Journeys

What does having access to college in prison mean to those who are incarcerated? How does it shape their perspective, their thinking, their lives?

The Emerson Prison Initiative (EPI) has been providing that access to men incarcerated at MCI-Concord since 2017, and graduated the program’s first cohort in September 2022. On Friday, March 24, EPI hosted a one-day conference on Innovation in Access and Equity for Incarcerated People in Massachusetts, featuring panels on data and analysis, and policy and legislation related to college in prison, as well as keynote speaker and poet/activist and 2021 MacArthur Fellow Reginald Dwayne Betts.

The day also featured a panel of four former EPI students, one of whom left prison with a degree and three who are finishing their programs on the Boston campus. The men talked about how college in prison worked, what led them to pursue a liberal arts education, the transition from college in prison to on campus, and how their education has shaped their lives, both inside and outside the carceral system.

What follows are excerpts, lightly edited for clarity, of the panelists’ answers to several questions asked by moderator Cara Moyer-Duncan, associate professor and EPI assistant director, as well as audience members.

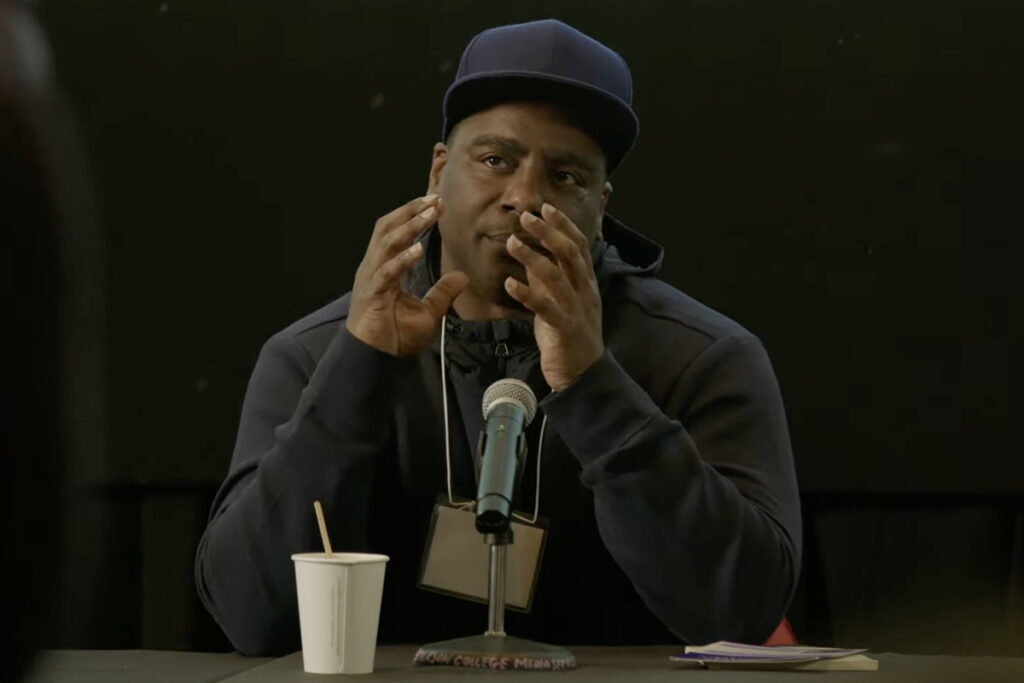

John Yang ’23

Emerson student

First EPI student to enroll on the Boston campus

“Through academics, I learned about social power structures and what this meant for those who didn’t understand [those structures]. With each EPI course, from Race and Ethnicity to Argument and Advocacy, I became better at understanding the social conditions of the world I was living in… The more I learned, the more I was gifted with avenues of creating and achieving the change I wanted to break away from the lifestyle I had believed I was restricted to.

“I have taken a minor in Nonprofit Communications. I wanted to continue to travel down that road [after graduating] and maybe [enter] some arena of post-incarceration work, social work. So maybe some more school. Until then, I don’t know.

“One of the hardest things to do [inside] was to get the resources and material we needed to do to get the studies done, [due to] complications with professors bringing in stacks of paper…. So if a professor came in with 150 pages of work and had to go through a three-day process … sometimes we didn’t get to see what our grade was for like three weeks. … So just being able to do that and go through things like that was a struggle.

“In prison, what we really did was we made being nerds a cool thing. And if people aren’t aware and people don’t know the opportunities [available to them], they don’t know what’s really out there. So what we really did was bring that awareness to the forefront and make it visible so that people can see their opportunities as well.

“I work at the Engagement Lab … and through that work study I was I was also was able to take a course Making Games for Change. [A]s students in the class, we were able to work with community members in developing a game for social change. I believe a concept like that is such a unique thing that can be brought into the classroom where you are learning from the community to how to effectively affect the community with change. I do believe that if we’re going to shift culture and create change, then we also need to create the way we teach as well. How can we learn to better our community if we don’t bring those from the community into the classrooms and learn what the problems are and then address these problems in a proper way?

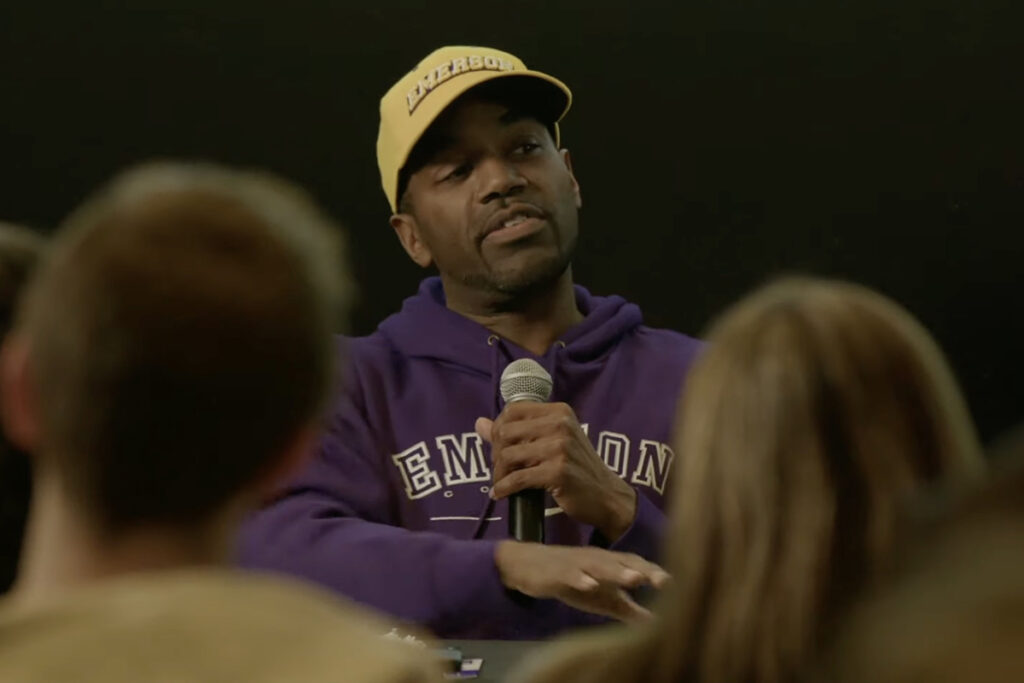

Mac Hudson ‘23

Community Liaison Coordinator, Racial Equity in Corrections Initiative

Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts

“I was familiar with how to access the courts, I was familiar how to access some legislators, but I wasn’t fully aware of the many ways that you can access those entities. And I think that, for me, is really what EPI gave me the ability to do, is to analyze in a way that took me out of my legal mode, and really gave me the discipline to step outside myself and to really kind of look at things in a more or less holistic point of view.

Even dealing with those various differences of opinion, how to navigate those conversations without feeling like it’s going to result in physical violence… that’s what you learned in the art of debate when we’re in class. You know, the emotions were very high sometimes, but we all understood we [were] in the academic space, which allowed for that. And because of that, we felt safe with one another and we grew.

“I read a lot of books … and it’s so true, is that first you got to get an understanding of who you are, what you are, where you come from, and link back to that understanding, because then you can also appreciate everything that you receive afterwards, the importance of it. So that was the first knowledge [I gained].

The second knowledge of reading, ways to understand systems, really did come through learning how to understand. And what I mean by that, for instance, we always say white and Black, but we don’t talk about how those things came into formation. We don’t talk about how whites became known as whites and what were they known [as] prior to that, and who came up with this system of ideas? Why did we start identifying Blacks under this racial hierarchy that we do in the manner in which we do?

“EPI has a re-entry component, and … has really [taken] a lot of steps to prepare me, my transition, and so that I would be comfortable in the classroom, how to navigate Canvas, you know, which is something new. I had never worked on a laptop, didn’t understand the components of those things. Even down to getting my license, which I had to take a few times, right? Everyone just worked together cohesively as a family. And that’s how I felt, like I was with my family, that I was getting things that I needed, getting the services that I needed.

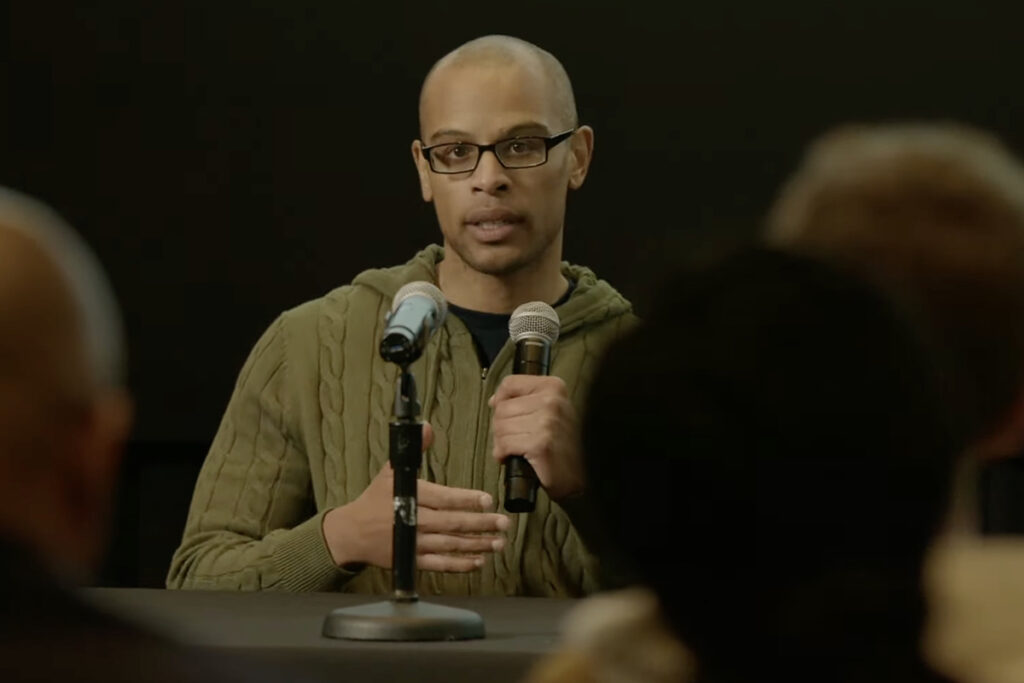

David Baxter ‘22

Youth Advocate, Roca Massachusetts

First EPI graduate to be released

“College in prison represented … a chance, not only … to recapture something that I felt I cheated myself out in the past, but as I started to understand education in the way that they [were] teaching us, it also started making me understand that I have a greater role [to play] that would reimagine what public safety looks like, and how that applies to … carceral systems, not only in Massachusetts, but throughout the nation. But overall and mainly, it was a chance to make something whole again that was voided in many ways. And that something I’m talking about is me.

“It wasn’t so much the degree itself, rather than the process that helped me. I had to undergo some serious stuff, because there was a time in my life when I adopted a subculture that would’ve not allowed me to sit here today. So it was through the process of self-knowledge first, and then coming into EPI to help me put that self-knowledge into perspective.

I did a lot of self-educating — books, reading — but it was this battalion of scholars that [EPI Director] Mneesha [Gellman] gave us access to that really gave you the aha moment: ‘Oh, I get it.’ Because if you ever tried to read Foucault on your own, you know, that’s a whole different language.

“And I love the way power operates covertly through systems, and I became in love with that [idea]. So in the work that I do in the community, my activism, my organizing, my youth work with Roca, [education] allows me to go into these systems and be a better version than I would be [otherwise]. So that I believe right now I lead in my work in numbers and promotion and … I believe EPI prepared me to be that way, to sit and analyze questions, see the situation and act, and act on it better than before EPI.

“[In prison] I was in and out of segregation. I was dealing with gangs….And then I met a brother right here [Hudson] … who saw a uniqueness in me that I did not even see in myself at the time. Who had a relentless pursuit, because he never gave up … And it was his mentorship, as well as my self-knowledge that he embarked me on, who sparked the flame for me to do that, to understand my role as a Black man in the world, in America, that ultimately led me. Because once the veil of ignorance is lifted, you can’t pull it back down and say, ‘I want to be ignorant.’

Ahmad Bright ’25

Emerson student

Co-Founder/Vice President, A Bright Future

“I first learned that I was going to be incarcerated while on a college tour in Atlanta at 17 years old, and it would be 10 or 12 years before I was actually able to enroll in college through EPI. So for me, EPI was almost like an opportunity to come full circle, or to kind of restart life while incarcerated, given the path that I was already kind of on.

But more than that, EPI also gifted me a community of peers that I didn’t have prior to EPI while incarcerated. [I]t just kind of reinforced the importance of being present in your own education, taking the initiative, asking questions, seeking out help when you don’t understand something. Because to the extent that you take ownership of your education, you’re going to just become a more educated person, but at the same time, you’re going to develop more tools that will then propel you to success upon completing your education.

“One course for me that gave me a greater understanding of how power operates in America and just like how systemic everything is, was Race and Ethnicity, a course taught by Dean [Amy] Ansell… It was very enlightening for me for a variety of reasons, but in particular… just [in] how foundational and fundamental race has been in structuring our society here in America. When you have a fuller understanding of that, you better understand all the implications of it and how deep-seated it is and how hard it is to kind of uproot because it’s so entrenched.

“Let’s say a fight occurred somewhere else, totally unrelated to any EPI student, but because … the running of EPI is tied to the running of the prison, we’re subject to all of the things that go along with the running of the prison. I remember distinctly there would be times where we had important things going on in that particular day, maybe giving a speech or maybe taking a quiz or a test, but we would be delayed because we had to wait for a ‘freeze-up,’ to be cleared before movement could resume. So definitely like a lot of things were out of our control, and that impeded our education, for sure. But I would say that the self-motivation that everyone brought, along with the teachers and the TAs, it didn’t stop us from doing what we needed to do.

“I think that what academic institutions can do for … formerly incarcerated college students is just make our presence more known on campus, so that people who might have a curiosity or people who might want to help know that they can, and that there’s an opportunity for them.

Categories