Teach-In on Race: Writer, Scholar Eve Ewing on ‘Time Folding Back in on Itself’

Members of the Emerson community came together virtually over Zoom last week to engage with each other and guests around issues of race, self-care, and creating art in a climate of inequity and violence during the College’s fifth Teach-In on Race, held March 18-19.

This year’s Teach-in, “The Year of Living Dangerously: Equity, Self-Care and the Pursuit of Justice,” unfolded days after a white man killed eight people, including six Asian women, in attacks in and around Atlanta, and following a year when systemic racism has been brutally exposed by COVID-19 and shocking violence.

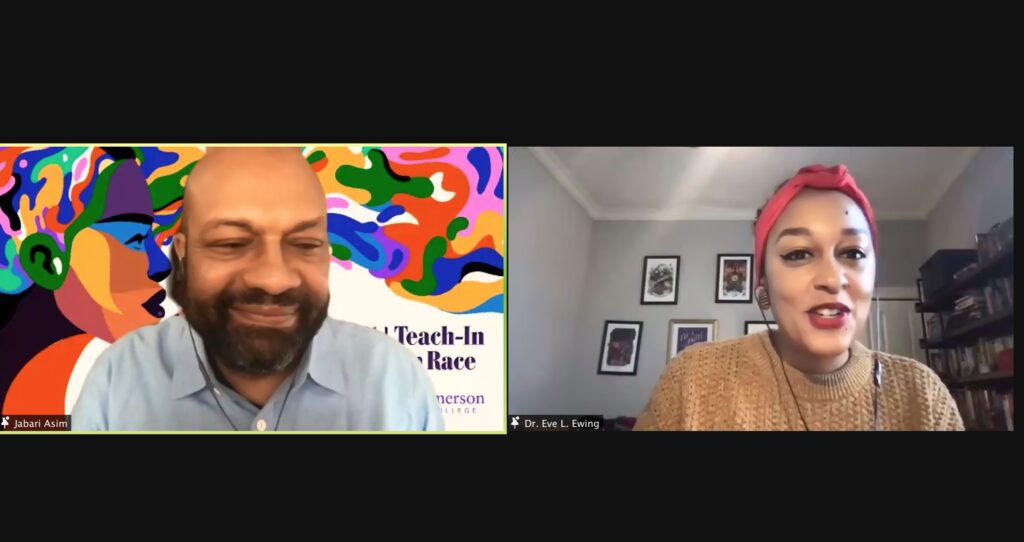

Dr. Eve Ewing, a writer, sociologist, and assistant professor at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration, was the keynote speaker for this year’s Teach-In.

Her poetry collection, 1919 (Haymarket Books, 2019) draws from a 1922 report, The Negro in Chicago, commissioned by the state of Illinois in the wake of racially motivated violence and uprisings during the summer of 1919. Each poem is a meditation on an excerpt from the document.

In her keynote speech, Ewing read several poems from the book, talked about the theories that underpin all her work, whether academic, literary, or theatrical, and answered questions from moderator Porsha Olayiwola, Boston Poet Laureate and Emerson community member, and the audience.

Excerpts from Ewing’s talk follow:

On ‘taking the boundaries of genre and freaking it’:

“I think that one of the biggest questions that I often get in Q&As is, ‘How do you think about moving across these different genres?’ or ‘How do you shift your brain or prepare in different ways to write a comic book, versus to write a poem, versus to write, you know, a script for a TV show?’ And I really struggle to answer that question, I’m probably the least well equipped person to answer it, because, to me, you know, it’s almost like being asked, ‘What is it like to eat cereal out of a bowl one day and then to eat ice cream out of a bowl one day?’ Like, how do you decide, right?

Well the vessel is the same vessel, it can be used in this multiplicity of ways. And I think that what the focus on genre can obscure is that I am more or less motivated by one simple question, or set of united questions. I see myself as a person with one project that takes on many parts, and I’m also trying to be united by a shared set of beliefs or ways of looking at the world. So the question that animates pretty much all of my work in one way or another is, ‘How did the world come to be as it is, and how could it be otherwise?”

On the importance of epistemology to the Black experience:

“If you are a person of color, and you experience something, an interaction in your daily life, and you felt like it was racist, the reason you feel like it’s racist is because you are drawing upon the entirety of your lived experience, a body of knowledge about what it means to move in the world in your body. … So you feel pretty confident that that comment, that that person, maybe it might feel innocuous or harmless to somebody else, it was racist — or homophobic or transphobic or ableist — whatever it is that you understand to be a grievous injury against yourself based on the lived knowledge you carry from the everyday reality of your life over the course of these years on this planet.

If you bring that to somebody else and you say, ‘You know, I experienced this thing, it was very harmful, they said this,’ and that person starts to question, ‘Well how did you know? How did they say it?’ …what they’re asking you for is evidence, and the counter claim that they’re making is your knowledge claim is inadequate, your basis of evidence for making this point is inadequate.

And that’s why questions of epistemology are so contentious, because how we define what we know, and who gets to define what knowledge is, is a question of our politics that plays out … in any kind of intellectual pursuit, any kind of pursuit of creativity, or the mind, or the body within which we might engage.”

On art and perspective:

“We can be urged into a space where we’re encouraged to talk about artistic practice as if it is divorced from the way in which we move through the world, and that’s impossible, because what [Toni Cade Bambara] is really saying here is that all artistic practice occurs within a political context, because we live within a political society, and we are political actors within that society.

Therefore, whether you choose to articulate it or not, your art is engaging in politics, so if that is the case, the question is, how do you make a conscientious decision about how you relate to the communities within which you are participating, what your accountability is to those communities? And what is the politics you choose to espouse? Because if your choice is nothing, something is always going to be projected upon the work that you do.”

On Afrofuturism and the nature of time:

“One of the things that about Afrofuturism that I think people misunderstand is that to me, Afrofuturism is not only about thinking through the literal future. It’s also about challenging the notion that time is linear at all. It’s about thinking about the ways that time folds back in on itself, and it’s evident to me that time folds back in on itself, or else I wouldn’t be able to write a book that has a poem about a 17-year-old boy dying in 1919 and a poem about a 17-year-old boy dying in 1953, and a poem about a 17-year-old boy dying in 2016. That there’s a way in which the Black life necessitates us thinking about the eternal return, about repetition, and about the relationship with the things that are allegedly passed, that are clearly not passed at all.”

On the Atlanta murders:

“This whole question of what happened this week — is it a hate crime, is it not a hate crime — to me, is so immaterial because there is no way of understanding what happened without understanding the environment, the ecology of violence, misogyny, white supremacy.

The assumption that you own people’s bodies, that you own certain types of people’s bodies, that you own Asian women’s bodies in a different way, that you are entitled to them and that they are objects for your consumption, and then if they refuse that consumption, that you are entitled to end their lives — there is no way of understanding that without understanding the milieu of white supremacy, patriarchy, misogyny.

The question of hate centered somewhere in in the individual, and what was in his heart and what was in his mind, that to me is so irrelevant because it’s the air you breathe, it’s the soil upon which you walk, it’s the terroir of the world in which you live. That is something that deserves and requires our interrogation, because until we understand that culture of violence, it persists as the organizing principle of our country and our society.”

Associate Professor Jabari Asim, Elma Lewis Distinguished Fellow and Graduate Program Director for the MFA Program in Creative Writing, founded and organizes the Teach-In with help from colleagues, the Honors Institute, the Elma Lewis Center, the Social Justice Center, and Academic Affairs.

Categories