Mann Stearns Award Helps Franklin-Lyons Experience Medieval Spain Via Mapping

Associate Professor Adam Franklin-Lyons wants to know how people in the Middle Ages communicated with each other across distances, so, with the help of a grant from Emerson, he’ll travel to Spain to gather 360-degree photos from strategic lookouts.

Franklin-Lyons, who teaches in the Marlboro Institute of Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies, is one of two faculty recipients of this year’s Norman and Irma Mann Stearns Distinguished Faculty Award.

Established by the late Dr. Norman Stearns and Emerson alumna Irma Mann Stearns ’67, this award honors a full-time tenured or tenure-track faculty member in recognition of outstanding scholarly or creative achievement. A $3,000 award is presented annually to at least one applicant. Funding may be used to enhance an ongoing project or for the development of a new scholarly or creative endeavor. Travel is strongly encouraged to be a part of the project activity.

Visual & Media Arts Assistant Professor Malic Amalya is this year’s other recipient. He will use the grant to travel to Florida to film at the Kennedy Space Center for his film in development, New Earth, a 16mm experimental documentary about the mythos of flight.

Franklin-Lyons will travel to Spain on the grant to gather a collection of 360-degree photos from strategic lookouts used during the medieval period, as part of his project entitled “Visualizing Networks of Medieval Communication: Photographs and Maps of Medieval Lookout Points.” The result will be an interactive map demonstrating the connections and limits of urban communication in the 14th-century Crown of Aragon.

He spoke with Emerson Today about the award, medieval times, traveling by horse, bandits, and more.

You’re traveling to Spain to take photos from 14th-century lookouts. Have you visited these places before?

Franklin-Lyons: I have visited several municipal archives, including Valencia and Barcelona. As an archival historian, I like this grant. This type of creative aspect isn’t something that gets funding.

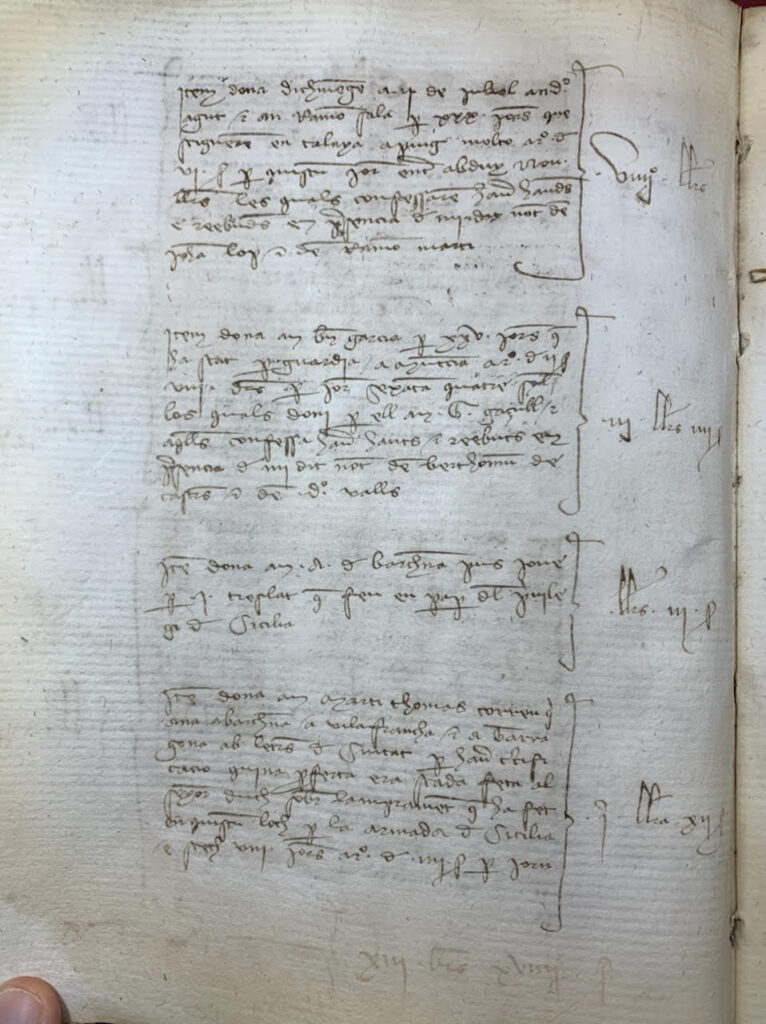

I’m going to Valencia, Barcelona, and Girona. There are documents that will say, ‘This person ran here this morning from this hill.’ I’m working on identifying more locations. There are hills up the coast where I know there’s a person stationed long-term, and if they see something they run back and tell people. That run can be 15 to 20 miles. What does that distance feel like? What does it feel like on the hill? Can you see the city? Can you see the next hill that has someone stationed?

I haven’t been to any of these places. I’ve been sitting in archive reading rooms. They don’t give a feel for what the route is like and what you can actually see. One location I’m visiting is in the Sierra de Montsià National Park near the city of Tortosa, which is 15 miles inland. It’s on one of the major navigable rivers.

I’m utilizing and translating notes from hundreds of years ago that are written in Catalan. In the early Middle Ages, in the time before Christopher Columbus in Spain, there were several different kingdoms, and each had their own slightly different language, like modern Spanish and Portuguese. As the kingdoms consolidated there were fewer languages. By the era I’m studying, there were essentially three, including Catalan.

When are you going?

Franklin-Lyons: I’m trying to figure that out. There are three options – I could go over winter break, spring break, or right after graduation next May.

You’re going to create an interactive map demonstrating the connections and limits of urban communication in the 14th-century Crown of Aragon. How will the map be used?

Franklin-Lyons: I get two main groups …asking questions.

One set of questions is usually from scholars. Right in the middle of this time period, 1391, there are a number of assaults on Jewish quarters, thousands of Jews across Spain are killed. Scholars tend to see this as a turning point in the idea of how Jews fit into Spanish culture. That sets up exile of 1492, when the Spanish kingdom formally removed Jews from the kingdom.

This priest from Seville kicks it off. The riots spread really fast. They start in Seville in southern Spain, and within days, there are riots in other cities. In a couple of weeks, Valencia has its own riot and they’re chanting the name of the priest who started it.

From information about the riots, we don’t know how the info moved so quickly, we just know it arrived. Also, it tends to catch scholars off guard, because it’s faster than we think it was — 40 or 50 miles a day, is the speed it moves, which is a really good clip in a world where it has to go by person. This work for me is a prototype of a larger project about tracking parcels of info across Spain in medieval times. What are expectations of how quickly info can move?

The second common question I get is from role players and historical novelists. They’re the people who want to describe daily life, the nuts and bolts, in very specific terms, and are looking up, for example, if you’re a miller in this town, who do you talk to on a daily basis? How much money do you make?

Novelists want to know if storylines are believable, like does it make sense that someone from London would end up in a particular location. They want to know minute details that a historian would gloss over versus the larger narrative. People email me, and ask, “Does this sound plausible to you?” I think that’s fun.

What inspired you to create this project?

Franklin-Lyons: I’ve been working with a group at Wesleyan for a while. They got me interested in mapping. I started learning about mapping when I was writing about famine. I thought mapping was moderately useful for famine.

I teach cartography and mapmaking at Emerson, also, and I love that class. I teach it with a mathematician, [Marlboro Institute Associate Professor] Matt Ollis. We look at medieval maps. …Students learn to make maps. We visit the Boston Public Library’s map room.

What kind of connections and limits of urban communication existed in the 14th century?

Franklin-Lyons: Fog, mountains. One thing I find interesting is the faster the movement, the lower the resolution. They used smoke signals, but those are sort of binary. The king had methods to inform whether an invasion was coming. You had 10 people set up fires on top of hills. You’re only sending yes or no. The news travelled potentially hundreds of miles a day. I’m also surprised I haven’t seen a higher use of pigeons. They don’t seem to use carrier birds from what I’ve found.

There are other restrictions on running. How far can someone really go in a day? What’s the weather like? How swampy is it? My suspicion is given travel times, the up and down of hills is less relevant than the weather or impediment by bandits, or safety of the route. If you’re going over a mountain, you’ve planned for it. It’s the unplanned things that have greater impact. They know how long it takes to get from Valenica from Teruel, which is way up in the mountains. Spain is very mountainous. Spain has the second highest elevation of European countries in the aggregate. Switzerland is first.

What will be on the map?

Franklin-Lyons: I want to have clusters of information associated with different routes. I want station points where people have been with the documented evidence of what I know from the archived documents. There needs to be some explanation as to why I put something on the map. It’s not a guess, but it is interpretative. Sometimes there’s strong evidence because some notes say it’s a particular location, outside of this town, and the town is still there and there’s a prominent point. That makes a lot of sense. Other times like the national park, the archival note says it the first prominent hill south of the river.

I want to include routes from city to city with documents. It’ll include photos that you can click on, and it would be neat to include which points you can see if you’re standing in a particular location. And from a particular photographed location, you can see another photographed location. On the map, for example, three points would light up to show that you can see them from a particular location. It would be cool to have a 360-degree photo and click into the photo.

Anything else you’d like to say about the award, your work, etc?

Franklin-Lyons: The Mann Stearns Award inspires experiential travel. I do intend to bike from point to point. I don’t have it in me to run 20 miles. But biking seems like a decent substitute. Bicycling gets me from point to point, and feel the full trajectory. I want to be able to explain that experience, not just describe what I’ve read in texts.

Categories