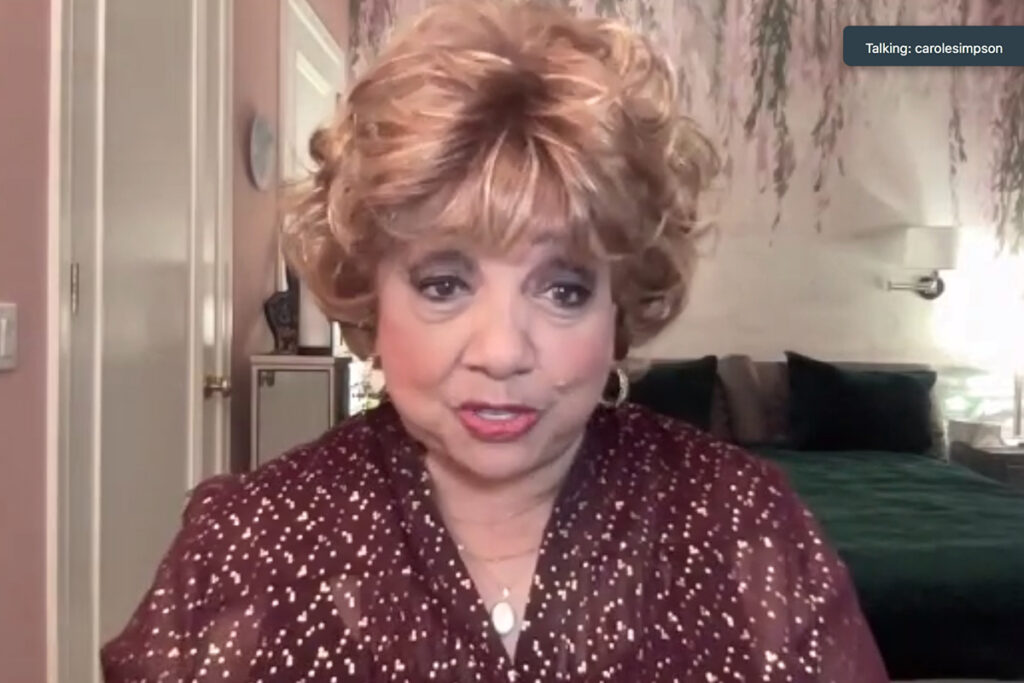

Pioneering Newswoman Carole Simpson on Perseverance and Making Trouble

Carole Simpson credits Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with igniting her career.

The three-time Emmy Award-winning reporter and anchor at ABC News and NBC News was a cub reporter for WCFL-FM, a CBS-affiliated news radio station in Chicago in January 1966 when her newsroom got word that King would be flying into O’Hare later that afternoon.

Nobody knew why the Civil Rights leader was heading north to Chicago, so her bosses sent her to track King down once he landed and ask him. After outsmarting the rest of the Chicago news corps and finding King at his hotel near the airport, she was told by his lieutenants that she’d have to wait until the press conference the next day to hear from the man like everyone else.

Simpson didn’t sneak onto the elevators and up to King’s floor just to leave without a scoop, so she spread out her winter coat on the cold tile floor and camped out near the elevators — all night long.

The next morning, she heard voices at the end of the hall and saw Dr. King walking toward her. He spotted her, stopped, and asked if she was the young lady he was told about – the one who waited all night to talk to him.

Simpson explained that she was there to find out what he was doing in Chicago. He told her there would be a press conference in a few hours, and she told him she wanted to beat her competitors. Then he leaned over and whispered in her ear that he was there to challenge the city’s segregated housing patterns and Mayor Daley’s refusal to do anything about it.

As he got on the elevator, Simpson said, he turned back and told her, “Young lady, I expect big things out of you one day. I appreciate your persistence and your perseverance. You’re going to do well.”

“Well, can you imagine how I felt?” Simpson asked students, faculty, and staff gathered on Zoom to hear from the groundbreaking journalist. “This is Dr. King telling me that I’m going to do well, and it was like throughout my career, I couldn’t let him down.”

Journalism affiliated faculty member Diane Mermigas hosted Simpson, a former distinguished journalist-in-residence at Emerson for 12 years, on Wednesday, February 8, so students could hear from her about breaking barriers as a Black woman journalist at a time when very few were given the opportunity to rise in the ranks.

During her remarkable career, Simpson reported on some of the biggest stories of the day: the Clarence Thomas-Anita Hill hearings, the Oklahoma City bombing, the Senate impeachment trial of President Bill Clinton, the release of South African civil rights leader Nelson Mandela, and the fall of Philippines dictator Ferdinand Marcos, to name a few. She was the first woman and the first person of color to moderate a presidential debate in 1992.

Here’s more of what Simpson shared:

‘You do what you have to do’

Simpson tried to get a job at a newspaper after graduating from the University of Michigan, but as a young, inexperienced, Black woman, she was finding that difficult. Finally, her former department chair found her a job teaching journalism and heading up the information office at Tuskegee Institute, a historically Black university in Alabama.

Her parents begged her not to go, and Simpson herself was hesitant.

“I was like, ‘Alabama? I can’t go to Alabama.’ This was 1962, stuff was heating up… the murders, the shootings, the lynchings. But it was the only job [offer] I had.

“You go where you can. If you want to be what you want to be, you do what you have to do.”

Coming from the upper Midwest, Simpson had encountered racism, but not segregation. In the South, she learned what it was like to travel in the back of a bus, to not be able to try on hats in a department store, to watch movies in a filthy balcony and bring your own popcorn because you weren’t allowed at the concession stand in the lobby. The experience steeled her for what was to come.

‘I started taking those no’s like vitamin pills’

Simpson got used to hearing “no” from her bosses who didn’t want to give her the big stories or the air time, largely because there were no Black female reporters to serve as templates.

“I started taking those no’s like vitamin pills, and I would swallow them, and they would give me energy to fight again, because my whole goal was, I’m gonna show you,” Simpson said.

In the 1970s, women like Simpson began making progress in the industry.

“All of us, I think, that were breaking these barriers in all of these different news organizations knew that you had to be good. You can’t be average. You cannot be mediocre and be a Black woman from the South Side of Chicago, you have to stand out,” Simpson said.

That meant producing the best work she was capable of and bringing in stories that were so good, they literally couldn’t say no.

“All women need to be [excellent] so they can’t slam the door in your face,” she said.

Even once she was successful, she was doubted

She spent the first part of her career fighting for the chance to prove she was good, but eventually, once she had success, some of her white, male colleagues began to see her as competition, Simpson said. They would say the only reason the networks chose her to do the news was because she was a Black woman.

“Well, did they ever think I did a good job? I did it for 15 years. I don’t think they would have let me speak to the nation under ABC’s auspices if I couldn’t do the job. But [critics] will do all kinds of little things to undermine your confidence, and you’ve just got to [not take it].”

‘I was trouble’

Her power is rooted in her “big mouth,” Simpson said. Once she had status in the business, she began speaking up about inequities, bad opportunities, shoddy reporting, a practice she traces back to her time in Tuskegee.

“I decided I would do what I could do where I was to help others come along, and that’s why I have six scholarships for women and minorities, I belong to all kinds of professional organizations, because I’m trying to give back to the profession.

“But I stand on the shoulders of those people who got their heads beaten in. [The late Civil Rights leader and U.S. Rep.] John Lewis talked about he was in trouble, but it was good trouble. Well that was me at ABC. I was trouble.”

Categories