‘Leaning Into Discomfort’ Through Mapplethorpe’s Photos

This piece is reposted from the ArtsEmerson Blog.

Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) is a multidisciplinary dive into the work of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, inviting audiences to experience his controversial work from fresh new perspectives. The piece meditates on these images by using other mediums to react to them — music, poetry, choral work, and performers on stage.

In a conversation with librettist korde arrington tuttle, it became clear that while this production certainly focuses on Mapplethorpe’s photography, it primarily serves as a prompt for larger discussions on queerness, intersectionality, and how we all lean into discomfort to discover something deeper about ourselves. As the recent San Francisco Chronicle review noted, “Triptych accomplishes what art does best, which is to serve as a pointer toward further thought.”

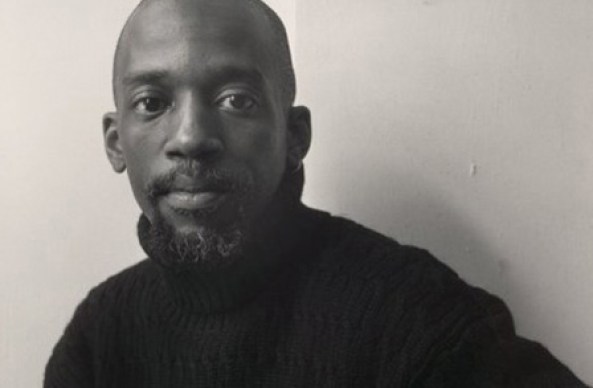

When tuttle first began working on Triptych, he started his process in the archives, dissecting Mapplethorpe’s artistic ethos through his work and related materials.

“I was blown away with what Robert saw, and I think what it allowed me to do was build a relationship with the archive, the subjects, with him, and with myself,” tuttle explains. “It allowed me to place myself on both sides of his lens and understand what he saw from his point of view, not just through the archive, but also through documentary work and interviews. It also helped me see his work as being a product of the American experiment.”

Through his own personal experiences and perspectives, tuttle aims to use Mapplethorpe’s portfolio to ignite dialogue between audiences and the art, looking toward the poetry of Patti Smith and Essex Hemphill to deepen the work.

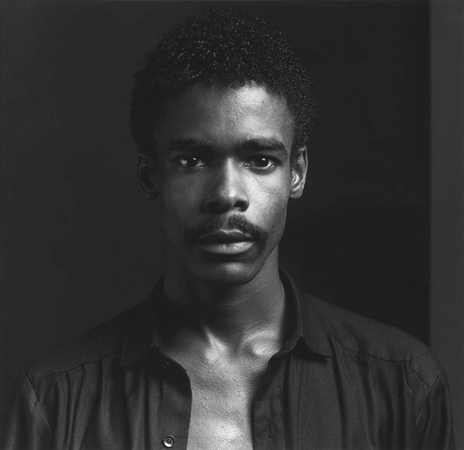

“The introduction of Essex Hemphill and his work and life became essential to my exploration,” explains tuttle. Hemphill was famously critical of Mapplethorpe’s photos, especially their use of black bodies. In his essay, “Does Your Momma Know About Me?” Hemphill argued that excluding the faces of the black men in the photos was a demonstration of fetishism by white members of the gay community.

“In his previously unpublished poem, “For Robert Mapplethorpe,” Essex poses a series of questions, but those questions are vital to properly framing his work,” tuttle says. This specific Hemphill poem, which asks, “Can aesthetics justify desire?” appears in its entirety in Triptych, set to music. It’s these moments in the performance when audiences can vividly witness tuttle openly asking questions about the rules of art in a broader sense, building upon Essex’s legacy.

Mapplethorpe’s career is often tightly connected with the controversy that originally surrounded it, such as critiques of his often graphic and explicit work, and his portraiture of black bodies. Retrospectives of Mapplethorpe’s photos have, traditionally, not delved deeply into the murky water of the intersectionality of blackness and queerness. This is the precise place, however, where tuttle interrogates his art and lyricism in Triptych.

“Being black and queer, and also having a relationship with whiteness and white queer men, intimately — understanding that power dynamic and the contradictions that exist when we talk about sexuality, desire, conditioning, and control — I felt as though I had not yet experienced any part of Mapplethorpe’s work that provided the models and subjects with agency,” tuttle said. “Particularly the black models, I wanted to humanize them in a way that filled in a larger picture of what it means to sit on either side of that lens.”

As a posthumous retribution, tuttle includes all of the names of the black models he could locate in the archives, not originally credited, and embeds them within the libretto.

So how does one honor and critique simultaneously? Can you push the narrative forward while still holding onto the past? And what to make of the current zeitgeist that suggests engaging with problematic artists in any form is a contribution to a toxic narrative?

“I take issue with this current cancel culture because I don’t think anyone is ever one thing,” tuttle said. “I have questions about accountability, for sure, but I also have questions about grace, complexity, and forgiveness.

“The first artist that comes to mind here is Kanye West. I have a lot of love for Kanye. And in his case, there are specific questions around mental health, but also invisibility and celebrity culture. Thinking about art and artists, like Kanye, like Mapplethorpe, I’ve had to attempt to reconcile my admiration, inspiration, and love, but also confront their words and actions that I find harmful. Because we are all one, all connected, the issues I take with Kanye are issues taken with myself. So, through Robert Mapplethorpe, I’ve had to look at myself and understand that I am not one thing. I have done things that I’m proud of and things that I’m not proud of. I’ve said things that I wish I hadn’t said, but I can’t unsay them.”

If tuttle had leaned towards the suggested path of cancel culture, he wouldn’t have taken on this Mapplethorpe project. But in turn, he wouldn’t have confronted his own shortcomings so head on.

“This process of healing and forgiveness, whether personal or collective, is about looking at all of it and being able to talk about all of it,” tuttle said. “Leaning in instead of leaning out has been very useful for me. I lean into discomfort, remaining there until a deeper truth emerges.”

At its heart, Triptych is far from a nostalgic look at an artist’s work, but a production for the present moment. While Mapplethorpe exists as a historical pinnacle, this work is not a biography. The production moves past antiquated ideologies, inviting people into the conversation. In Triptych, there is a unique chance to address topics surrounding Mapplethorpe that were previously avoided.

“I think the challenge is that Mapplethorpe is seemingly from a different time and era, and opera is seemingly from a different time and era,” tuttle said. “Black people need to know this is for them. Young folks, young queer folks, need to know this is for them. This is a story about right now.”

True to ArtsEmerson’s mission, we are ready to embark on this journey and begin these necessary conversations around art, healing, and progress. It is equal parts thrilling and terrifying, wandering into these territories, but we don’t go there alone.

“If you want to ask real questions and lean into discomfort with me,” tuttle offers, “we can hold hands together and ask deeply American questions. Let’s go.”

Triptych (Eyes of One on Another) runs at the Cutler Majestic Theatre through Sunday, November 3. Tickets available here.

Categories